Discipline is King Crimson’s eighth studio album.

Formed in 1969, King Crimson soon after their debut album In The Court Of The Crimson King ended up being fronted by guitarist Robert Fripp. Crimson released seven studio albums with varying line-ups until Fripp unexpectedly decided to break up the band ”permanently” after the 1974 release of Red. In 1974, rock listeners might have believed Fripp’s ultimatum, but as we have since learned, nothing in the rock world is permanent. King Crimson also returned seven years later on 22 September.

The return of the Red-era line-up had already been discussed in 1977. Fripp was planning a band called League Of Gentlemen, in which he, Bill Bruford and John Wetton would be joined by violinist/keyboardist Eddie Jobson. However, Fripp eventually backed out of the project and Bruford, Wetton and Jobson formed U.K. with guitarist Allan Holdsworth.

Between Red and the failed League Of Gentleman project, Fripp had almost completely withdrawn from the music business for almost two years. He became interested in the teachings of the philosopher G. I. Gurdjieff, which he studied under the eccentric spiritual mentor John G. Bennett in monastic surroundings.

Read also: Review: King Crimson – Islands (1971)

Around 1976/1977 Fripp began to make a return to music. However, instead of forming his own band, he concentrated on being a session guitarist and producer. Fripp played guitar on Peter Gabriel’s first three solo albums (and produced the middle one) and appeared on David Bowie’s ”Heroes” and Brian Eno’s solo albums. He also produced singer Daryl Hall’s first solo album, Sacred Songs, and around the same time began work on his first solo album, Exposure.

Exposure, released in 1979, was an excellent and eclectic art rock album inspired by the New Wave. It was followed by God Save the Queen/Under Heavy Manners (1980), which consisted mainly of Frippertronics guitar, and The League of Gentlemen (1981), which contained a strange disco-rock sound and had a familiar name. The League of Gentlemen’s B-side label included the cryptic text: ’THE NEXT STEP IS DISCIPLINE’.

Bill Bruford had been involved in a lot after King Crimson broke up. He had played with Gong, Genesis, National Health and others before co-founding the aforementioned U.K. After U.K. he put together his own band which released three excellent and distinctive jazz-rock albums Feels Good To Me (1978), One Of A Kind (1979) and Gradually Going Tornado (1980). After the third album, it became clear that running his own band was becoming financially impossible. The timing was perfect for Bruford when Fripp unexpectedly contacted him and suggested forming a new band.

Bruford suggested American Jeff Berlin as bass player. The virtuoso Berlin had played in Bruford’s band for the past few years so he would have been a natural choice, but the auditions didn’t really convince Fripp who found the nimble-fingered bassist’s style a little too nimble. So Bruford and Fripp auditioned bassists in New York for two days without success until Tony Levin took the stage on the third day.

The classically trained American Levin was an old acquaintance of Fripp’s, having played not only on Peter Gabriel’s second solo album produced by Fripp but also on Fripp’s own Exposure. Fripp has since said that Levin would have been his first choice as bassist, but he automatically assumed that the busy studio ace would not be interested in joining any band on a permanent basis (in fact, in the late 70s Fripp and Hall had toyed with the idea of forming a joint band with Levin and drummer Jerry Marotta as rhythm section players). Levin, however, had been tired of the shallow role of session musician for some time and was looking for new challenges. Previous collaboration with Fripp had shown that this would be a very attractive direction from which to start looking for them. Levin was an excellent choice for the band as the classically trained bassist had technique to spare, but he was also an excellent groove player who was at home not only in art music but also in rock, pop and jazz. In fact, Levin is one of those rare players who can easily be imagined playing almost any genre of music.

There was still another guitarist missing from the puzzle. From the beginning, the guitarist’s place in King Crimson had belonged only to Robert Fripp and founding member Ian McDonald has said that ”When you have Bob Fripp in the band you don’t play guitar”. However, Fripp’s fresh vision of a rock gamelan required a second guitar with which to play polyrhythmic guitar patterns.

He had caught the eye of American guitarist Adrian Belew, who had inherited his place on David Bowie’s ”Heroes” tour after Fripp turned down the honour. Fripp was impressed not only by Belew’s effortless and skilful technique, but also by the guitarist’s energetic way of performing. Fripp and Belew first met when they went together with Bowie to see Steve Reich’s band perform material from the Music For 18 Musicians album. In retrospect, this gig was quite a remarkable event. It was a combination of Fripp’s key musical influence for years to come and a meeting with a musician with whom a fruitful collaboration would continue for three decades.

Born in Kentucky, Belew started out playing drums, but switched to guitar at the age of 16. Some years later, Belew ended up supporting himself as a member of an entertainment band that toured playing in hotel lobbies across the US. Guitarist/composer Frank Zappa happened to see the band playing at the Holiday Inn in Nashville in 1977.

The young Belew, already a skilled guitarist at the time, impressed the demanding Zappa. Belew joined Zappa’s band and played the original composer’s challenging music on tour for about a year and was also included on the 1979 studio album Sheik Yerbouti (although largely based on material recorded in concert). Belew would probably have stayed with Zappa’s band longer if Brian Eno hadn’t tipped off David Bowie about him. Major Tom, as a disgruntled Zappa called Bowie, made Belew an offer he, as a big Bowie fan, could not refuse.

Belew jumped on the Bowie bandwagon, playing guitar parts Fripp had recorded in the studio only a short time ago on a tour to promote the ”Heroes” album. Belew put his own stamp on Bowie’s output with the final part of the Berlin trilogy, Lodger (1979).

When Fripp asked Belew to join his band for the first time, Belew refused as he was busy touring and recording with Talking Heads. At Eno’s invitation, Belew had played on a few Remain In Light songs and toured with the band as an unofficial member. However, Belew soon realised that there would be no place for him as a composer in Talking Heads so when Fripp called again a few months later the answer was yes. On the condition that Belew would also have time to invest in his nascent solo career.

Fripp’s new quartet was assembled and after a short practice it started touring in small venues under the name Discipline on a trial basis. The band’s repertoire from the beginning included not only completely new material but also a few old King Crimson songs such as ”Lark’s Tongues In Aspic Part II” and ”Red”, which Crimson had never actually played live before their break-up.

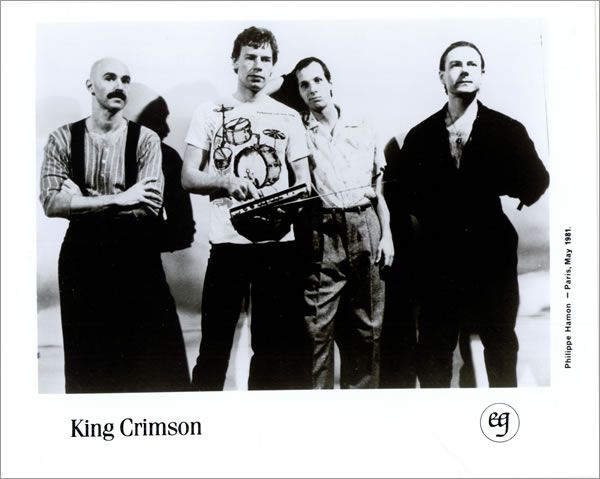

The Discipline shows were well received and Fripp was thrilled. So thrilled, in fact, that he was ready to call the band King Crimson after all. This quartet was worthy of the famous name, which was important to Fripp. Of course, commercial realities also weighed in favour of this decision. The power of the King Crimson name had only grown over the years and it was clear that this name would attract far more attention than starting from scratch. The people at EG, Fripp’s record label, clapped their hairy hands in excitement at the decision.

A reborn King Crimson began recording their new album in May 1981. Since good ideas are not wasted, the album was called Discipline. Discipline was produced with the help of outside ears for the first time in the band’s history. The credit went to Rhett Davies who had worked as a recording engineer or producer with Genesis, Camel, Talking Heads and Roxy Music. As producer of Discipline, Davis’ role was mainly to ensure that the brand new King Crimson sound was captured on tape in the best possible quality and hopefully in a commercially viable way. Artistically, this foursome were more than capable of producing themselves. The album was efficiently recorded in three weeks at Island Studios.

Lue myös: Levyarvio: King Crimson – Starless and Bible Black (1974)

So what is King Crimson’s new sound and fresh style on Discipline? At any rate, quite different from the band’s previous album, Red, released seven years earlier. Whereas the King Crimson of the 70s was inspired by early 20th century art music and jazz, the King Crimson of the 80s is influenced by Indonesian gamelan music, the minimalism of Steve Reich, Philip Glass and similar modern composers, and the new wave and no wave rock that Fripp had discovered on the streets of New York after moving there in the late 70s. Gamelan’s influence is particularly evident in Fripp and Belew’s intricate repetitive guitar patterns that intertwine. Often in a polyrhythmic way.

Fripp also took a leaf out of Peter Gabriel’s playbook and, like Gabriel on his third solo album, urged Bruford to avoid using cymbals as much as possible. Fripp’s idea was that this would free up frequencies in the soundstage for his and Belew’s bright and clean guitars and generally simplify the sound in an interesting way. This is exactly what happened, but the added bonus was that when a skilled musician is put under constraints he usually finds a way to do something interesting and this is certainly the case with Bruford.

New technologies play an important role in Discipline. Each member of the band brings the latest gadgets to the table in a natural way. Bruford has Simmons’ electric drums as a seamless companion to the acoustic drums, Levin plays an instrument called the Stick, which, depending on the version, is either a 10-string or a 12-string instrument that looks like a piece of plank that is tapped instead of plucked, and which, because of its wide range, is capable of playing both the traditional role of the bass guitar and, if necessary, providing a third melodic instrument alongside Fripp and Belew’s guitars. Fripp and Belew both make extensive use of guitar synthesizers on the album, forging new sounds alongside traditional guitar sounds or sometimes sounding like a trumpet or a jungle animal. It’s worth noting that while in the 80’s the role of keyboards became more prominent in almost every band, Crimson didn’t use them at all on Discipline, even though it might sound that way on a superficial listen.

The overall sound of Discipline is modern (by 80’s standards) and more refined than King Crimson’s usual sound. On the surface, this makes the music feel confusingly pop at times, but in fact it is every bit as complex as the band has always been expected to be. Especially the rhythmic sophistication of the album is really impressive. The songs are full of irregular time signatures which are often used in a polyrhythmic way. As the name of the album suggests, the music is very controlled and precise. Occasionally, however, it explodes into chaos. Belew counterbalances Fripp’s restrained control with brashness and energy. Belew’s singing is fine (with a slightly David Byrne-esque quality that has led to overdone Talking Heads references) and his original and inventive guitar playing is on the same virtuosic level as the rest of the band.

”Elephant Talk”, which kicks off the album with a bang, introduces a renewed King Crimson in one fell swoop, kicking the bags sharply for those Crimson fans who were expecting to hear a sobbing Mellotron and a pastoral flute. The music of ”Elephant Talk” is avant-garde mutant funk that feels downright danceable thanks to Levin’s bass groove. It’s miles away from King Crimson’s 70s material, but still, I for one have never had any difficulty accepting it as King Crimson music.

Belew makes a strong first impression as he performs the lyrics with neurotic fury, half singing, half talking, while simultaneously strumming his guitar synthesizer to make great elephantine sounds. Belew’s vocals consist of an alphabetical list (from a to e) of communicative words that he recites in an increasingly nervous tone. Towards the end, the fourth wall cracks with a crash as Belew exclaims ”These are words with a D this time!”.

Halfway through ”Elephan Talk” Fripp plays, also using a guitar synthesizer, a short warbling guitar solo that is at once lyrical and very strange. The song’s second solo towards the end of the song is a wailing and bending with a more tortured sound and sounds a bit like the solos Fripp used to play in the late 70s when he was in ”new wave mode”, but in fact the soloist has changed to Belew! This is a good example of how in Discipline’s dense music it is often difficult to tell who is playing what, especially when the typical sound of the instruments has often been transformed by modern technology into something completely different. It is Belew who has often suffered from this lack of transparency, as many Crimson fans have automatically assumed that many of the parts played by Belew are the work of Fripp’s hands. I have occasionally fallen into this trap, despite the fact that I have the highest regard for Belew.

The album’s second track ”Frame By Frame” represents in a way the most rocky part of the album, but at the same time it effectively presents Fripp’s vision of the rock gamelan. Fripp and Belew’s staggeringly paced patterns, mostly featuring bright tones, wrap around each other with mathematical precision in different time signatures. Only now and then rhythmically meeting each other. A fast, futuristic-sounding pulse beats in the background. One of the most impressive aspects of ’Frame By Frame’ is the way Belew has managed to weave a very catchy and natural vocal melody into the very complex music. In fact, Belew is the agent throughout the album that insidiously brings humanity and grip to otherwise avant-garde music that even the casual rock music listener can pick up on.

After two quite intense songs, the atmosphere calms down at just the right moment with ”Matte Kudasai” (the name is Japanese for ”please wait”). The gently melancholic ”Matte Kudesai” may at first seem like very un-Crimson-like music, but in fact ballads have been part of the band’s repertoire from the very beginning. Of course, they have often been more epic in nature than ”Matte Kudesai” which is more small-scale and intimate in style.

Belew’s strong and clear vocal voice in ”Matte Kudesai” seems to channel more David Bowie than the David Byrne he is usually compared to. In fact, ”Matte Kudasai” is actually an art rock ballad that would have fitted quite nicely on one of the albums of the Bowie Berlin trilogy that Fripp and Belew both contributed to. ”Matte Kudasai” is a beautiful and atmospheric song that provides a nice little respite in the middle of an otherwise intense album.

”Matte Kudasai” was released as a single, but it didn’t make much of a splash for the album, failing to make the major sales charts.

The album’s fourth track ”Indiscipline” is the song that finally lets Bruford really loose. So far on the album, Bruford’s playing has been relatively restrained, but on ”Indiscipline” he positively solos his way through (and even gets to hit cymbals). Bruford’s unruly ”overplaying” on the track feels like he’s releasing all the pent-up energy that he generated when Fripp insisted on his previous minimalist approach. ”Indiscipline” is Bruford’s sweet revenge! ”Indiscipline” is also one of the songs on the album and one that clearly references the band’s history for its angularity and a certain fearsomeness. ”Indiscipline” also features Fripp’s furiously buzzing atonal distorted guitar solo that would have been easy to imagine for Red’s successor if one had appeared in, say, 1975.

With Bruford terrorising the rhythm in every possible way, the rhythmisation of the song on a macro level is left to Belew’s spoken word. In his lyrics, Belew describes some kind of mysterious object to the listener, emphatically hoping at the end that the recipient will see it. What it is, however, is never made clear, but the song ends with Belew’s passionate exclamation ”I like it!”. Personally, I could exclaim the same about ”Indiscipline”. A truly stunning song. One of King Crimson’s best.

(In fact, the lyrics of ”Indiscipline” were inspired by a letter from Belew’s wife describing a painting she had just painted. However, it is impossible to deduce this just by listening to the lyrics.)

Read also:

- Review: Michael Oldfield – Heaven’s Open (1991)

- Review: Talk Talk – The Colour Of Spring (1986)

- Levyarvio: Jeff Wayne – Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version Of The War Of The Worlds (1978)

- Review: Gong – Shamal (1976)

- Review: Genesis – A Trick Of The Tail (1976)

- Review: Rush – Moving Pictures (1981)

”Indiscipline” kicked the album into high gear and the next track ”Thela Hun Ginjeet” doesn’t exactly put the brakes on. Levin’s thick-sounding bass guitar constantly gives the song a mercurial ostinato over which Bruford tapping his drums vividly accentuates the song’s rhythms that ripple in the cross-pressure of Fripp’s 7/8 guitar patterns and Levin and Belew’s 4/4 rhythm.

As a vocalist, Belew is even more clearly back in the speak-singing mode than before. Actually, it’s not even a song, but a real-life story that he told in an agitated state of mind in the studio to the whole band. Fortunately, Fripp secretly recorded Belew’s outburst and it was eventually woven into the music with such ingenuity that it makes the man’s storytelling sound almost song-like. In any case, the end result is extremely musical and, unlike what often happens to such spoken word pieces in music, it hasn’t started to bore me even after dozens of listens.

Belew’s story is also interesting in itself. Belew was wandering the streets of London recording background vocals for a possible song when a bunch of menacing gridiron youths stopped an American who was strangely sneaking around their block with a tape recorder. The alleged gang members questioned Belew menacingly and his situation was not helped when he was forced to play back the contents of his tape recorder, which included the phrases ”he was holding a gun in his hand” and ”this is a dangerous place”, which further confused the harassers of the guitarist who was working on musique concrète. Eventually, however, Belew was let go and, as he strode towards the studio, relieved but still frightened, he was met at the first street corner by two squads of patrol officers. This caused Belew to burst into nervous laughter in the middle of his story. Such a great moment!

After Belew’s laughter, the song, which has been slowly building up to this point, reaches its climax and culminates in Belew’s repeated exclamation of ”thela hun ginjeet”. The cry, which sounds like an African language, is not in fact a language at all, but an anagram of the working title of the song, ’heat in the jungle’.

After two furious songs, the mood changes radically. At just over eight minutes, and the longest track on the album, ”The Sheltering Sky” is a floating, minimalist track. ”The Sheltering Sky” was improvised at a very early stage when the four were just getting to know each other musically during the practice phase.

”The Sheltering Sky” has a hypnotically gentle wooden slit drum of African origin played by Bruford in the background. To counterbalance the almost relaxing rhythm track, Fripp creates tension with exotic guitar synth sounds that sound a bit like a combination of trumpet and snake charmer’s flute.

The album ends with a title track that again returns strongly to Fripp’s vision of the modern rock gamelan. In a restrained, but inexorable, forward lurching track, Bruford maintains a loping 17/16 time signature through the top of his drum kit while anchoring the music with the steady 4/4 beat of the bass drum. This creates an interesting tension which is further emphasised by the guitar patterns of Fripp and Belew, which tick around each other in a number of different irregular time signatures. At no point do any of the individual instruments take the lead, but the different instruments form a seamless and disciplined clockwork where each sound supports the other. The precision with which the musicians operate amidst the complex rhythms is staggering. Steadily increasing in intensity towards the end, ”Discipline” is a fascinating song and has inspired many later bands such as Nik Bärtsch’s Ronin and especially Sonar, whose whole style seems to be based on the lessons of ”Discipline”.

Few bands that have died out have returned as vibrantly and radically renewed, yet still retaining their essential character, as King Crimson with Discipline. Discipline is one of King Crimson’s most significant albums and a bold start to a new era for the band.

Discipline received a largely positive reception when it was released, but it seems that the album was still not fully understood when it was first released. The appreciation of the album has grown over the decades. Even though some Crimson fans still deeply dislike it. Countless experimental rock bands, and especially the so-called math rock bands, have drawn inspiration from it, and Discipline’s innovations survived to some extent on all of King Crimson’s subsequent albums.

Best tracks: “Elephant Talk”, ”Frame By Frame”“Indiscipline””Thela Hun Ginjeet” ja “Discipline”

Read also: Review: King Crimson: Three Of A Perfect Pair (1984)

Author: JANNE YLIRUUSI

Tracks

- ”Elephant Talk” 4:43

- ”Frame by Frame” 5:09

- ”Matte Kudasai” 3:47

- ”Indiscipline” 4:33

- ”Thela Hun Ginjeet” 6:26

- ”The Sheltering Sky” 8:22

- ”Discipline” 5:13

King Crimson

Adrian Belew: electric guitars, guitar synths, vocals Robert Fripp: electric guitars, guitar synths, gadgets Tony Levin: Chapman Stick, bass guitar, backing vocals Bill Bruford: drums, slit drum, percussion

Jätä kommentti