Heaven’s Open is Mike Oldfield’s 14th studio album.

Oldfield’s previous album, Amarok, released a year earlier, had been a middle finger to Oldfield’s record label, Virgin. The label’s demands for more commercial music frustrated Oldfield so much that Amarok became a 60-minute snub to his paymasters. Amarok was an uninterrupted hour-long complex musical roller coaster from which it was deliberately impossible to extract the singles Virgin craved. Amarok was also a gift to Oldfield’s devoted fans who longed for long instrumental pieces, which were undoubtedly the maestro’s strongest suit.

If fans were expecting Oldfield to make a permanent return to purely instrumental music after Amarok, Heaven’s Open was a cold shower for them. Heaven’s Open is in many ways a return to the old style, but not quite in the way many fans might have hoped. Heaven’s Open returns to the format familiar from Crises and Islands, where one half of the album consists of short pop/rock songs and the other half is filled with long instrumentals. In other words, a format that Oldfield has described in roughly the following terms: ”half for them (the record company) and half for me.” That’s fine, life is full of compromises. Unfortunately, Heaven’s Open implements the format with somewhat uneven material.

Heaven’s Open is basically a step or even two backwards after Amarok, and it would be easy to criticize the album as a lazy interim work, but in at least one area it offers something completely new and shows that Oldfield did not just throw the album together with his left hand. Heaven’s Open is the first album on which Oldfield takes responsibility for the lead vocals.

Oldfield approached singing seriously and took singing lessons for several months to prepare for the project. Oldfield sings Heaven’s Open with a slightly hoarse voice and a fairly narrow range, but his voice is charismatic and ultimately has a surprising amount of power. And, above all, emotion.

A stronger emotional impact and personal touch set Heaven’s Open apart from Oldfield’s previous pop music. In terms of lyrics, this is probably Oldfield’s most personal album, as he seems to pour his heart out in an exceptional way. The lyrics are full of the angst Oldfield feels about his own situation. And of course, the fact that he sings his own lyrics this time around nicely emphasizes the personal nature of the album. Oldfield’s vocal performances are easily on the plus side, and as far as I’m concerned, he should have sung more on his albums. In practice, however, Oldfield never returned as lead vocalist after Heaven’s Open. The 2014 album Man On The Rocks would have been a good place to return to vocals, but by that point it was probably too late.

Read also: Review: Mike Oldfield – The Songs Of Distant Earth (1994)

Musically, the songs on Heaven’s Open are a bit more rock-oriented than, say, the pop songs on Islands and Earth Moving, but the biggest difference between them is on an emotional level. With Heaven’s Open, Oldfield returns to a slightly more band-like sound. With Earth Moving, the background was largely built with drum machines and sequencers.

Heaven’s Open’s core band consists of Oldfield’s old friend Simon Phillips (drums), Dave Levy (bass), and Mickey Simmonds (keyboards and piano), who played in Fish’s band. In smaller roles on the album, Andrew Longhurst plays keyboards and samples, and Courtney Pine, a saxophonist who was on the rise in the early 90s, also makes an appearance. There is also a small army of female singers supporting Oldfield’s vocals.

Oldfield, who swears by music played by hand on the Amarok, dug out his computers again for Heaven’s Open, and at times the band seems to get lost among the various programmed rhythm tracks and bleeps. For example, the first track on the album, “Make Make,” sounds as if it was probably constructed almost entirely by Oldfield alone in the studio. Only the bass track, which sounds suspiciously like thumb bass, is likely to be the work of Dave Levy.

Two of the vocal tracks on side A stand out in particular.

The first of these is the dark and atmospheric ”No Dream,” which begins as a subdued blues song and gradually builds toward a rousing finale. Pine’s saxophone buzzes with a wonderfully dirty sound, and Oldfield’s guitar responds to the challenge with a strongly effected, screeching sound, while Phillips pounds out powerful drum fills in the background. Oldfield’s emphatic vocal performance is also successful.

Another highlight is the title track on side A. ”Heaven’s Open” is basically a pretty corny AOR anthem. But it’s an extremely entertaining one! It features the most memorable melodies on the album and a damn fine, galaxy-shattering finale. As I have stated in several of my previous writings, Oldfield is skilled at crafting spectacular climaxes for his songs. These massive, explosive climaxes occur naturally in his long instrumental epics, which allow room for development, but in the case of ”Heaven’s Open,” he manages to build a rather spectacular finale even in a song with a pop/rock structure and scale. Oldfield’s ferociously screaming electric guitar combines massively with the girl choir roaring in the background and a successful overall increase in volume.

Heaven’s Open never sounds as polished as Amarok, but Tom Newman still did a good job on this album. The album was probably made in a bit of a hurry, as it was released just over six months after Amarok. Newman is the sole producer credited on Heaven’s Open, which is actually the first time Oldfield did not claim that title, even jointly.

Oldfield has said that he got tips for ”Heaven’s Open” from David Gilmour himself. Tom Newman was a good friend of the Pink Floyd guitarist, and Oldfield ended up jamming with Gilmour a few times in a pub. After one such jam session, Oldfield complained that he was having problems with a particular song. Gilmour offered to listen to the song and apparently gave such good tips that Oldfield recalled in an interview that Gilmour even received producer credit for the song. However, according to the album booklet and other written sources, this does not seem to be the case. But wouldn’t it have been great to happen upon a pub where Oldfield and Gilmour were jamming together in the corner! According to Newman, these jams sometimes escalated into quite a competition.

The weakest track on the album is ”Gimme Back,” where Oldfield jumps on the reggae bandwagon ten years late compared to other white British rockers. In this song, too, the personal nature of the lyrics raises the score slightly. (Simmonds’ light Hammond organ accompaniment in the background is also a nice addition. The Hammond is not often heard on Oldfield’s albums.) Of course, the lyrics in which Oldfield roughly equates his position as an artist struggling under the yoke of a record company with slavery can be seen as the whining of a millionaire musician, but a genuine feeling is always a genuine feeling, even if, objectively speaking, it may not be entirely justified!

I need my hair

I want my voice

Gimme my vision

Gimme back my choice

Oh, here I hang on this hook, line, and sinker

Don’t take the skin off my fingers

The opening track ”Make Make” and ”Mr. Shame” represent the more mediocre, but still quite acceptable, side of the album.

With its strong electronic sound, and in that sense most reminiscent of Earth Moving’s songs, ”Make Make” seems to be a general protest against capitalism, but it takes a direct jab at Virgin, which is always pushing more products onto the market.

Mona Lisa you can stop searching

Don’t you know we’re not Virgin

We’re on the Make Make

We only Take Take

We’re on the Make Make

We accumulate

We’re on the Make Make

Don’t mid it’s Fake Fake

We’re on the Make Make

We make heartbreak

Mr. Shame, with its catchy chorus, feels like a direct message to Virgin’s main man, Richard Branson (on Amarok, Oldfield already sent Branson a message in Morse code: ”Fuck off RB”). In this song, spiced up with comical synthesizer riffs that sound like they were stolen from Peter Gabriel’s ”Sledgehammer,” Oldfield sings with a playful grin, ”Are you a victim of that money bug/In your blood?” In the chorus, Oldfield is successfully assisted by female vocalists singing in the background.

The balance on side A is reasonable. Musically, the songs are stronger than Oldfield’s average pop offerings, and the lyrics in particular rise slightly above the mediocrity that often characterizes the man’s songs. The lyrics may not be great poetry, but at least this time they have something to say. And Oldfield’s emotional vocal performances give them weight.

Read also

- Levyarvio: Gong – Zero To Infinity (2000)

- Review: Michael Oldfield – Heaven’s Open (1991)

- Review: Talk Talk – The Colour Of Spring (1986)

- Levyarvio: Jeff Wayne – Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version Of The War Of The Worlds (1978)

- Review: Gong – Shamal (1976)

- Review: Genesis – A Trick Of The Tail (1976)

And then there is Oldfield’s real bread and butter: large-scale instrumental music. This is provided by the album’s closing track, the nearly 20-minute-long ”Music From The Balcony,” which contains perhaps Oldfield’s most avant-garde material. ”Music From The Balcony” continues the carefree attitude of ”Amarok” towards musical structures and is, in a way, stylistically similar to Amarok Jr. Both works strike a fast pace, moving from one musical idea to the next with a carefree attitude.

However, there are also significant differences between ’”Amarok” and ”Music From The Balcony”. Both stylistic and qualitative. A clear stylistic difference is that while ”Amarok” largely avoided synthesizers and modern technology, ”Music From The Balcony” is full of noisy samples and strange synthesizer sounds.

Amarok was also largely Oldfield’s one-man show, but ”Music From The Balcony” features some pretty intense band playing between the synthetic antics. At times, the band consisting of Oldfield, drummer Phillips, bassist Levy, and saxophonist Pine plays together like a fiery jazz-rock quartet. Unfortunately, these moments are not given much space, as the song often moves quickly on to a completely new theme. Some of the band’s playing is truly excellent, and ”Music From The Balcony” contains some of the wildest and most complex musical moments on Oldfield’s albums. Simon Phillips in particular gives his all when the rhythms are at their most intricate. It’s wonderful to hear.

The strange samples and sound effects in the song are also great to listen to at times. In particular, the strange bird and monkey-like cries that recur throughout the work as a kind of theme are really strange and fascinating to listen to. I know that many people dislike these parts, but I find them genuinely interesting to listen to.

Overall, however, Music From The Balcony is not entirely convincing. Or let’s say that its effectiveness depends largely on the attitude with which I happen to listen to it. If I listen to it as a normal Mike Oldfield epic, its constant jumps and leaps are distracting and confusing, but on the other hand, if you think of it as an avant-garde sound collage, ”Music From The Balcony” is actually a pretty interesting experiment. However, it is clear that, in terms of quality, ”Music From The Balcony” cannot compete with ”Amarok”, which juxtaposed seemingly incompatible elements in a more careful and refined manner. Nevertheless, I appreciate the energy and uncompromising attitude of ”Music From The Balcony”. At the end of ”Music From The Balcony”, we hear a small, very quietly mixed chuckle and Oldfield’s final farewell to Virgin: ”Fuck off!”

There are a couple of interesting musical facts associated with Heaven’s Open.

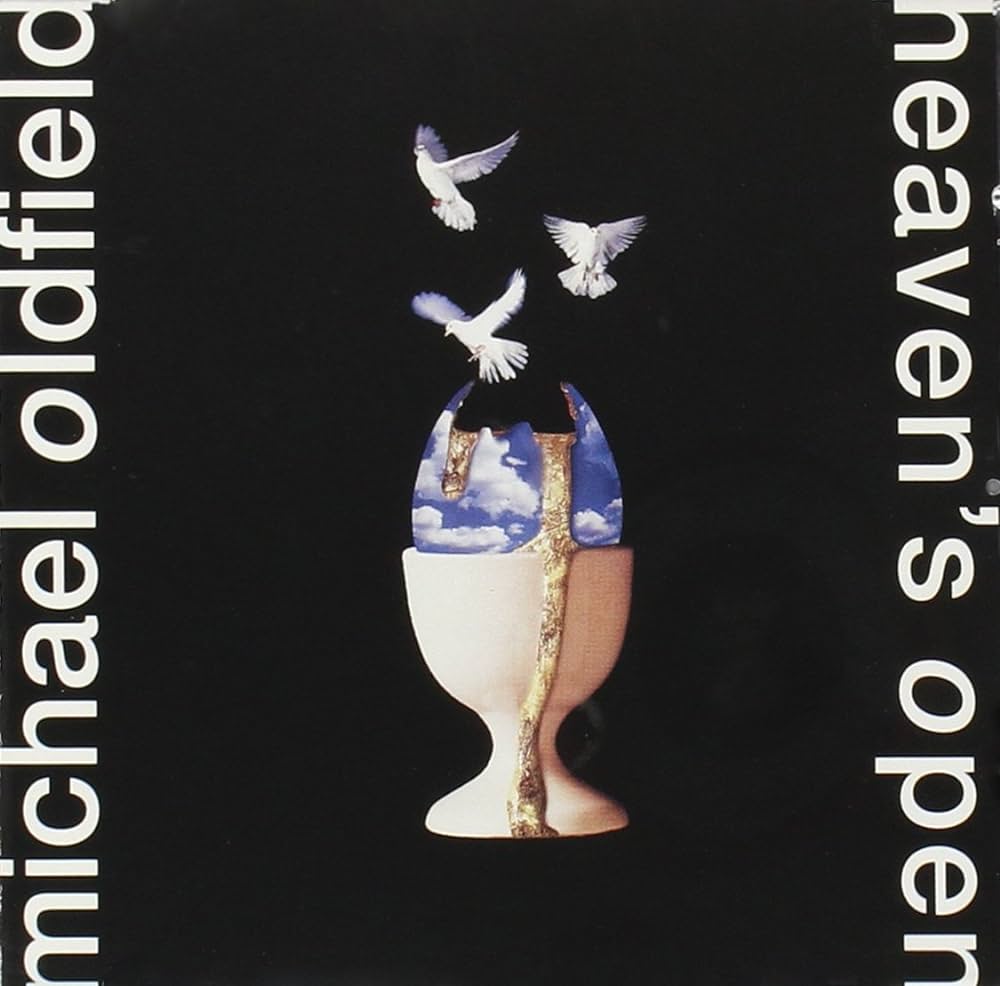

The first is the album cover. In 1973, Richard Branson suggested the name Breakfast in Bed for the as-yet-untitled Tubular Bells. Branson wanted the cover to feature a broken egg with blood dripping from the crack in the shell. Oldfield hated both ideas and, as we know, fortunately got his way when it came to the album’s name and cover art. But lo and behold, in 1991, the cover of Oldfield’s last album recorded for Virgin bears a striking resemblance to Branson’s old idea. The cover features an egg with yolk oozing from the crack instead of blood, and three doves flying out of the egg into freedom. Another one of Oldfield’s many middle fingers to Branson?

Another interesting thing is that the album is credited not to Mike Oldfield, but to Michael Oldfield. Producer Tom Newman also appears on the album under the unusual name Thom Newman. I have never seen any clear explanation for this practice. A few possibilities come to mind. Perhaps Oldfield wanted to release the album under his real birth name due to its personal nature? Perhaps Oldfield planned to sing more in the future and these albums would have been credited to Michael Oldfield, while the instrumental albums would have been credited to Mike Oldfield. Or perhaps, on the contrary, Oldfield wanted to distance himself from the album, which he considered his last compromise before gaining freedom when his contract with Virgin ended. Or maybe Oldfield simply didn’t want to give Virgin any more Mike Oldfield albums, and Michael was just one of his ways of sulking? Either way, Heaven’s Open remained the only album released under the name Michael Oldfield. I asked Tom Newman about this directly. His laconic reply was, ”Just a bit of self-indulgence…”

Heaven’s Open is not a particularly good Mike Oldfield album (well, it is a Michael Oldfield album…), but I still think it is a surprisingly successful pop/rock album, coated with the experimentalism of ”Music From The Balcony”. In my own books, I even consider the album to be somewhat underrated. In terms of general appreciation, the problem with the album may be its strong duality. Some of Oldfield’s followers are wary of his view of middle-of-the-road pop, while for others, ”Music From The Balcony” is far too avant-garde to listen to.

Heaven’s Open sold poorly and didn’t even make it onto the album charts in Britain, but this hardly bothered Oldfield, as he already had a lucrative new contract with Warner Music in his back pocket and the bells were already ringing in his head, predicting a new and better future…

Best tracks: ”Make Make”, ”No Dream”, ”Heaven’s Open”, ”Music From The Balcony”

Author: JANNE YLIRUUSI

Read also: Review: Mike Oldfield – Exposed (1979)

Tracks

- ”Make Make” – 4:18

- ”No Dream” – 6:02

- ”Mr. Shame” – 4:22

- ”Gimme Back” – 4:12

- ”Heaven’s Open” – 4:31

- ”Music from the Balcony” – 19:44

Musicians

Michael Oldfield: vocals, guitars, keyboards Simon Phillips: drums Dave Levy: bass guitar Mickey Simmond: Hammond organ, piano Andrew Longhurst: keyboards, sequencing and samples Courtney Pine: saxophones, bass clarinet Vicki St. James: backing vocals Sylvia Mason-James: backing vocals Dolly James: backing vocals Debi Doss: backing vocals Shirlie Roden: backing vocals Valeria Etienne: backing vocals Anita Hegerland: vocal harmonies Nikki ”B” Bentley: vocal harmonies Tom Newman: vocal harmonies

Jätä kommentti