Shamal is the sixth studio album by Gong, founded in 1967.

Gong’s previous album, You (1974), was a tremendous artistic success, but after its release, the band itself was in turmoil. There were philosophical (some of which involved illegal substances) and musical conflicts between the band members, which ultimately led to a minor fistfight and the departure of keyboardist Tim Blake. A little later, beat mystic Daevid Allen, who had not only founded the band but was also its main visionary, left Gong. Shortly after this, vocalist Gilly Smith was replaced by Hillage’s girlfriend Miguette Giraudy, who had already made a small appearance on the band’s album You.

Guitarist Steve Hillage was the obvious candidate to succeed Allen, and at first it seemed that he might even be interested in taking his mentor’s place as leader of Gong. However, after a brief period of searching, Hillage became more interested in his solo career, which he had begun in 1975 with his excellent album Fish Rising. Hillage was still fully involved in the tour of England that followed You, during which songs intended for the band’s next album were tested (these live versions can be heard on the excellent album Live In Sherwood Forest ’75, released in 2005). However, when the recording of Shamal finally began in October 1975, both Hillage and Giraudy had decided to leave the band. Nevertheless, both appear as guest musicians on the album, Hillage on two tracks and Giraudy on one.

Read also: Review: New York Gong – About Time (1980)

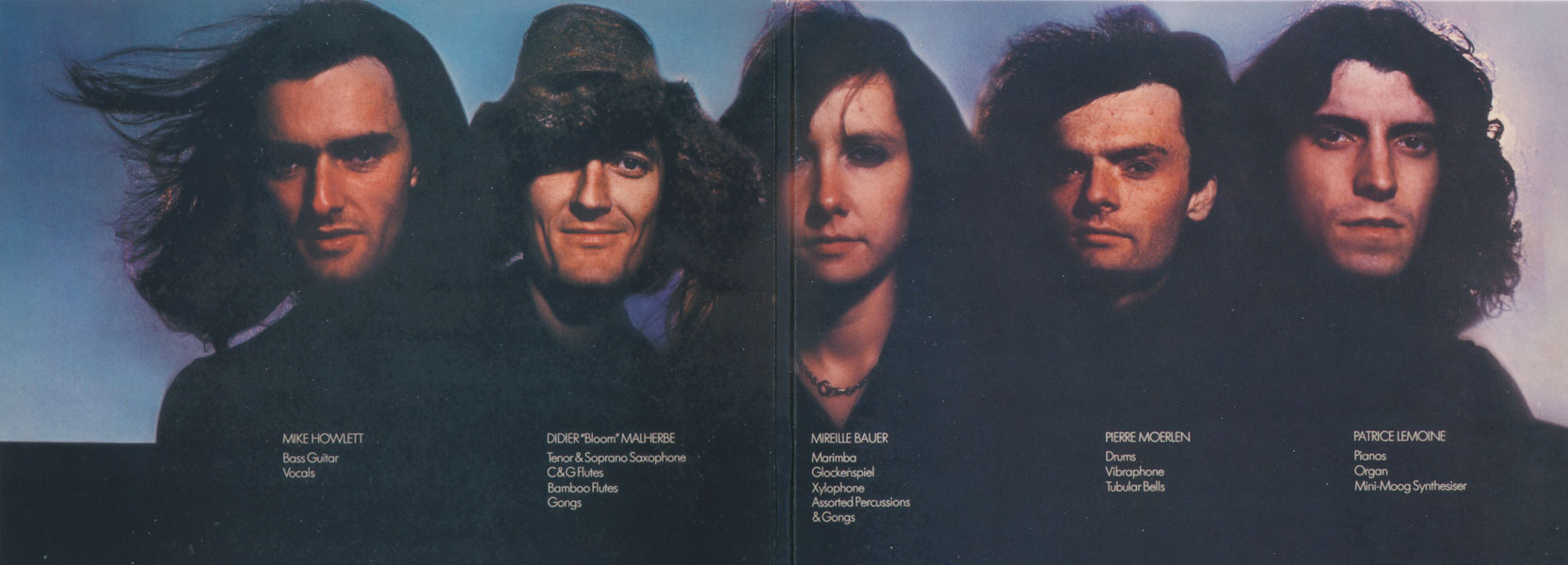

With Allen and Hillage gone, Gong was left without a clear leader for the first time in its history. The new Gong was formed around three strong instrumentalists. Versatile wind player Didier Malberbe had played with Gong from the beginning, and bassist Mike Howlett and drummer/percussionist Pierre Moerlen had formed the band’s equally powerful and agile rhythm section since 1973. However, while Howlett had not missed a single gig since joining, Moerlen had already left Gong a few times and then rejoined on several occasions (Moerlen was replaced at times by such formidable drummers as Chris Cutler, Laurie Allan, Bill Bruford, and Brian Davison).

In addition to the core trio, the band was joined by percussionist Mireille Bauer, who had already appeared on You, and keyboardist Patrice Lemoine, who was relatively new compared to the other musicians (and who had once tipped off his compatriot Moerlen about a vacant drum seat in Gong). Throughout Shamal, Lemoine is a stylish background player, accompanying the band with effective, understated virtuosity rather than soloing. In contrast, classically trained Argentine violinist Jorge Pinchevsky (who previously played in the French band Clearlight) gets and takes more solo space, and his fiery playing brings a whole new spicy flavor to the band’s sound.

However, Pinchevsky’s violin is by no means the only innovation on Shamal, released in the spring of 1976. The sound and style of Shamal is completely different from that of You. The sound of the album is, if not acoustic, then at least semi-acoustic. Whereas on You the electric guitar and bubbling synthesizers dominated, on Shamal the solo parts are played mainly by Malherbe’s versatile collection of wind instruments, various tuned percussion instruments, and Pinchevsky’s violin. Hillage’s electric guitar makes a few stylish cameo appearances.

The music also has strong ethnic influences, which are particularly evident in Malherbe’s playing, but these elements are also built into the compositions themselves. If You was a perfect collision of jazz-rock and space-rock, Shamal just as skillfully combines jazz-rock with influences from ethnic music. Ethnic influences are sought from many different directions, mainly from Asia and South America. In a way, Gong moves in much the same territory as the Finnish band Piirpauke on Shamal, even though the end result is very different.

Wingful Of Eyes

The album kicks off with “Wingful Of Eyes,” which is probably a calculated move in the sense that it’s the only song on the album that even remotely resembles the band’s previous work. The song serves as a gentle nod to old fans and a welcome to the world of Shamal. The combination of the low rumbling bass and high-pitched chimes in the first half of ”Wingful Of Eyes” is irresistible. Didier Malherbe’s ethnic wind instruments add their own gentle flavor to the mix. Soon the song picks up speed, shifting into a tight groove (Mike Howlett is probably the grooviest bassist ever heard in British prog) and Steve Hillage plays guitar with an uncharacteristically rough touch. Bassist Howlett sings psychedelic nonsense lyrics with surprising conviction. The lyrics and vocals are no match for Daevid Allen, but Howlett does a competent job as the band’s new vocalist. However, apart from the opening track, the vocals are only heard briefly in a couple of other songs. ”Wingful Of Eyes,” composed by Mike Howlett, seems to be trying to channel the mood of Allen’s Gong period in some way, but it also drifts delightfully into a completely different mood in the end.

Chandra

Composed by the band’s new keyboardist Patrice Lemoine and with lyrics by Howlett, ”Chandra” kicks off with a rumbling bass riff, over which Malherbe stylishly blows his saxophone while Moerlen drives the whole thing forward with his tight drumming. Bell chimes, xylophones, and marimbas eventually join in, foreshadowing the greater role these instruments will play on Gong’s subsequent albums. ”Chandra” grooves and swings forward with real style and a kind of ease, even though it is clear throughout that this group consists of nothing but virtuosos (well, except perhaps Lemoine). At around four and a half minutes, Pinchevsky plays a robust violin solo, which signals Howlett’s vocals to come in. The vocals bring a hint of rock to this strange ethno-jazz vibe, and strangely enough, the eclectic mix works really well. Howlett is accompanied by Malherbe’s tenor saxophone and Mireille Bauer’s xylophones. If ”Wingful Of Eyes” still had a slight resemblance to the old Gong, ”Chandra” is something completely different.

Bambooji

The A-side of the album concludes with Didier Malherbe’s ”Bambooji,” which begins with the sound of wind, chimes, and a lightly whistling ethnic flute. The mood seems to refer to somewhere in the Andes mountains. Miquette Giraudy sings wordless vocals and the bells ring even more intensely, while Malherbe once again plays some kind of ethnic wind instrument which, judging by the credits, is probably a bansuri, a flute made of bamboo that is popular in India. Moerlen’s drums come in strong at around two and a half minutes, and the music becomes more hectic jazz-rock with Hillage’s lively guitar strumming and Pinchevsky’s strangely thin violin riff. Then the music stops for a moment and the mood returns to the mountains of South America, almost reminiscent of that classic coffee commercial that all Finnish children of the 80s remember. Not exactly a pleasant association, but that’s not Malherbe’s fault, and this music is still awesome!

”He has always been, and remains, the best musician Gong ever had. He is a true virtuoso – but to the point that he never shows it” – Daevid Allen Didier Malherbesta vuonna 1977

Cat in Clark’s Shoes

Malherbe, Lemoinen, and Howlett’s joint composition ”Cat in Clark’s Shoes” is a playful song full of surprising twists, stops, and starts, as well as changes in tempo and style. The song begins with a bouncy bass riff and is full of tight ensemble playing, but also features some fine solo performances, most notably Pinchevsky’s elegant but crisp violin and Malherbe’s tooting on numerous wind instruments. Shortly before the six-minute mark, this already incredibly rich song suddenly turns into a tango. Thankfully, it is an Argentine tango and not a Finnish one. And perhaps the tango twist is not so surprising, given that the band includes a genuine Argentine violinist. Adding local color to the tango atmosphere are the lines recited in the background, apparently in Spanish, in a seductive style (the content of which, with my language skills, could be anything from a gingerbread recipe to car repair instructions). ”Cat in Clark’s Shoes” proves that it is possible to mix elements from almost any genre into progressive rock and make it work.

Mandrake

Moerlen’s composition ”Mandrake” begins calmly with vibraphone, light snare drum rolls, and Malherbe’s flute. The beautiful, and again somewhat ethnic, flute melody carries the song for the first couple of minutes until, at the two-minute mark, the music explodes into a more energetic jazz rock, driven by Moerlen’s tight drumming, with Malherbe soloing on soprano saxophone and Mireille Bauer playing cyclical gamelan-inspired patterns on the marimba in the background. ”Mandrake” clearly foreshadows Gong’s subsequent albums, which would be made specifically under Moerlen’s artistic direction.

Shamal

The album concludes magnificently with the nine-minute “Shamal,” a joint composition by the band. The song begins with tight jazz-rock, with Malherbe soloing tastefully on tenor saxophone over Howlett and Moerlen’s truly delightful comping. In the middle section, vocals are added in the form of a duet between Howlett and guest vocalist Sandy Colley. Howlett’s rhythmically simple, occasionally word-dropping, low voice is mixed right on the surface, while Colley’s more intense, fast, almost shouting vocals are buried deep within the soundscape. The contrast is effective. After the vocal section, we hear a lightning-fast and perhaps overly short marimba solo from Bauer, immediately followed by a fierce violin solo from Pinchevsky. Pinchevsky was an excellent addition to Gong’s sound, and it’s a shame that he didn’t become a longer-term member of the band. Pinchevsky apparently intended to join the band, but he was caught at the border on a tour with a violin case full of weed, which ended his tour and his job with the band. David Cross from King Crimson was considered as a replacement, but before this could happen, the Shamal lineup had already broken up for good. At the very end of ”Shamal,” Colley’s vocals hypnotically repeat a single phrase as Moerlen’s drums explode with magnificent fills, accompanied by Malherbe’s roaring saxophone. A magnificent ending to a magnificent album.

Shamal does not contain a single weak or even mediocre track; its diverse and rich music works wonderfully from start to finish. The album is a truly successful change of direction for the band, and the difference is so great that I understand it may leave some fans of Gong’s earlier albums scratching their heads in wonder. For me, its unique combination of prog, jazz-rock, and ethnic tones works perfectly. I don’t know of any other album like it, and Gong itself boldly forged ahead on new paths with its subsequent albums. I mentioned that Piirpauke’s first albums are perhaps some kind of distant kindred spirits, but perhaps the closest to Shamal’s style is the Frenchman Rahmann’s eponymous debut from 1980. Its ethnically flavored jazz-rock moves in much the same sector as Shamal.

American avant-garde jazz composer/pianist Carla Bley was initially considered as the producer for Shamal, but in the end the job went to Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason, who already had Robert Wyatt’s masterful album Rock Bottom (1974) under his belt. I believe this was the right decision because, although Bley is a masterful musician, I don’t think she would have been able to conjure up sounds as luxurious as Mason’s on the album.

I don’t know how much Mason contributed to the actual artistic side of the album, but at least on the technical side, he and his sound engineers (there were no fewer than five different engineers involved) did a brilliant job. Shamal’s mixes are first-rate. Due to the wide range of instruments, mixing must have been a challenging task, but Mason and his team succeeded perfectly. Each instrument has clearly been recorded with great care, and they all sound crystal clear and distinct. However, they never sound detached or floating apart from each other, but always serve the whole. Mason clearly understands the importance of layering in mixing. Not everything has to sound evenly on the surface; some instruments can dive quite deep into the soundscape and still make a big impact when the whole is carefully thought out so that not too many instruments operating at the same frequency compete for space at the same time. In my opinion, Shamal is one of the best albums of the 1970s in terms of sound. The luxurious soundscape of Shamal comes into its own in the 2018 version, remastered by Simon Heyworth with care and respect.

Read also:

- Levyarvio: Jimmy Page – Outrider (1988)

- Review: Brian Eno + David Byrne – My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1981)

- Levyarvio: Gong – Zero To Infinity (2000)

- Review: Michael Oldfield – Heaven’s Open (1991)

- Review: Talk Talk – The Colour Of Spring (1986)

- Levyarvio: Jeff Wayne – Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version Of The War Of The Worlds (1978)

- Review: Gong – Shamal (1976)

- Review: Genesis – A Trick Of The Tail (1976)

- Review: Rush – Moving Pictures (1981)

Shamal is clearly a transitional album. It no longer belongs naturally to Daevid Allen’s hazy space rock period. On the other hand, it is not yet pure jazz rock, which is what the band became at the end of the same year with the album Gazeuse!, directed by Pierre Moerlen. Unfortunately, the Shamal lineup soon broke up after the album’s release due to old familiar conflicts. Moerlen and Bauer wanted to make completely instrumental music, while Howlett and Lemoine wanted to add more vocals. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, the record company Virgin ended up supporting Moerlen’s instrumental approach. Perhaps they were tempted by the success of jazz-rock greats Weather Report and Return To Forever.

However, Shamali’s trump card is precisely its eclecticism. An important part of its unique charm is that it is very difficult to define it as belonging to any particular genre. Broadly speaking, it is progressive rock, but at the same time it is so far removed from the admittedly broad mainstream of that genre that even that definition does not do the album justice. Neither Gong nor anyone else has ever made another album quite like Shamal. As much as I love David Allen’s original vision of Gong’s music, for me, Shamal is not only Gong’s best album, but also one of the best albums of all time. Shamal is a masterpiece.

Best songs: The whole album is brilliant, I can’t leave any songs out.

Author: JANNE YLIRUUSI

Tracks:

Side A

1. ”Wingful of Eyes” 8:19

2. ”Chandra” 7:16

3. ”Bambooji” 5:21

Side B

4. ”Cat in Clark’s Shoes” 7:45

5. ”Mandrake” 5:07

6. ”Shamal” 8:58

Gong:

Mike Howlett: bass, vocals Didier Malherbe: tenor saxophone, soprano saxophone, flutes, bansuri, gongs Mireille Bauer: marimba, glockenspiel, xylophone, percussion, gongs Pierre Moerlen: drums, vibraphone, tubular bells Patrice Lemoine: organ, electric piano, piano, Mini-Moog

Guests

Steve Hillage: acoustic guitar, electric guitar (”Bambooji” and ”Wingful of Eyes”) Miquette Giraudy: vocals (”Bambooji”) Jorge Pinchevsky: violin Sandy Colley : vocals (”Shamal”)

Producer: Nick Mason

Jätä kommentti