The Division Bell is Pink Floyd’s 14th studio album.

Many would argue that The Final Cut (1983), which was Roger Waters’ last Pink Floyd album, should really have been called Waters’ solo album. Perhaps so, but in that case the first Floyd album, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, made under guitarist David Gilmour, should also have been credited to Gilmour. However, The Division Bell, released seven years later, is more easy to accept as a true Pink Floyd album.

Released in 1987, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason was made with the help of an army of studio musicians and outside lyricists. Pink Floyd founding member drummer Nick Mason plays very little on the album, and the last-minute addition of co-founding member keyboardist Rick Wright, who had been kicked out of the band around the time of The Wall, was allowed to play one barely audible solo. Gilmour and Bob Ezrin, who produced the album, tried hard to make an album that sounded like Pink Floyd, but the result sounded forced. Entertaining enough, but superficial and somewhat mechanical. Even a bit soulless.

However, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason’s nuanced take on Pink Floyd music struck a chord with the masses. The album was a huge success and Gilmour and Mason, who had partly financed the album with their own money, could breathe a sigh of relief. Especially as the tour that followed the album was an even bigger success. The tour resulted in the recording of Delicate Sound Of Thunder (1988), a live album of clunky versions of old Floyd classics. Which was… well you guessed it, a huge success.

This hat trick empowered Gilmour, which ultimately works to the listener’s advantage with The Division Bell. Gilmour had won over the fans and legitimised his position as the new leader of Pink Floyd. And when the legal battles over the Pink Floyd name with Roger Waters were, at least for the time being, over, the mood was more liberated in that respect too. The Division Bell is in every way a more relaxed and natural album than its predecessor.

Rick Wright was reinstated as an official member of the band when recording sessions for The Division Bell began. But with a weaker deal than Gilmour and Mason, who became senior partners. This soured Wright that the keyboard player, who had once been a founding member of Pink Floyd, was about to walk away from the whole project. Fortunately, this was not the case, as Wright’s hand is very much in evidence on the album in a positive sense, and he was credited on no less than five songs.

Although the importance of outside forces on The Division Bell is considerably less than on the previous album, there is one new major outside force on the album.

Gilmour’s new girlfriend (the couple married in 1994 after The Division Bell was completed), journalist Polly Samson, takes on a surprisingly large role on the album. Samson encouraged Gilmour to get off cocaine, instilled confidence and helped the guitarist in his weakest area, lyric writing. Samson was involved in writing the lyrics to no less than seven songs, so in terms of pure credits his importance on The Division Bell was even greater than Wright’s. Not to mention Mason who only played drums. But at least this time his drum tracks got to stay on the final album unlike on A Momentary Lapse Of Reason!

Samson didn’t come up with any particularly stunning lyrics, but overall the lyrics are more apt, interesting and above all personal than the vague vapidity of the previous album. It seems that Samson was able to open up and write about things that really mattered to him, which is reflected in a positive way in the engaging lyrics.

Musically, Floyd, led by Gilmour, still balances somewhere between slick stadium rock for adult tastes and progressive rock. The ’80s sounds have been mostly stripped away and the more organic soundworld of the previous album seems to be deliberately reaching towards The Dark Side Of The Moon and Wish You Were Here. All the weird and really experimental choices have been cleaned up, though. There’s nothing about The Division Bell that would cause anxiety in the ear of a top-40 chart-digging companion. Hundreds of bells don’t ring oppressively like in ”Time”, synths don’t roar aggressively like in ”Welcome To The Machine” and nobody howls orgasmically like guest vocalist Clare Torry did unforgettably in ”The Great Gig in the Sky”.

Like A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, The Division Bell begins with a melancholic and sparse instrumental. Slowly kicking off with electronic crackles and hazy synths, ’Cluster One’ clearly aims to anchor the album somewhere in the golden days of Wish You Were Here, and spin a yarn to the audience; ”yes, you’re listening to Pink Floyd now”. The melodic piano adds a touch of melody, but ultimately ’Cluster One’ falls short of being a harmless wallpaper of sound. In one ear, out the other.

Opening with a thick bass riff (Guy Pratt on bass guitar) and funky electric piano, the second track ”What Do You Want From Me” represents the rockiest side of the album. On The Wall, we heard the tasty rock parody ”Young Lust” and ”What Do You Want From Me” is more or less in the same vein. This time, though, it’s serious. Not a bad song, but in the end a rather generic blues-influenced rock. Gilmour’s lively guitar playing and the ooo-aaa vocals of the three female vocalists do, however, add a little spice.

In the lyrics, Gilmour recounts the tough demands he faced and some of the lines (Should I sing until I can’t sing anymore?/Play these strings ’til my fingers are raw?) made me think for a long time that the song was aimed at over-demanding Floyd fans. This always amazed me because fans have treated Gilmour, unlike Waters, with kid gloves and settled for very little. Apparently, however, Gilmour directed his frustration more towards his new partner Samson. What wasn’t he singing about me and other fans? Boring!

The third track ”Poles Apart” is the second longest track on the album and one of its most successful. At seven minutes long, ”Poles Apart” is effortlessly paced largely on Gilmour’s gentle acoustic guitar. Gilmour sings superbly with a soft yet powerful voice. Wright gets to play a subtle and elegant Hammond solo. In the middle of the song we hear a slightly disconnected ghostly fairground sequence of the kind that Steve Hackett favours in his own music. Fortunately, Floyd does the circus thing a little more elegantly than the former Genesis guitarist. At the end, Gilmour grabs the spotlight back on himself with a long, sweeping guitar solo.

In the lyrics of ”Poles Apart”, Gilmour reminisces about former Floyd members. The first verse laments the harsh fate of Syd Barrett (and mirrors Gilmour’s own success) and the second verse marvels at Waters’ ruthlessness.

Did you know

It was all going to go so wrong for you?

And did you see

It was all going to be so right for me?

Why did we tell you then

You were always the golden boy then

And that you’d never lose that light in your eyes?

The album’s second instrumental ”Marooned” which, like ”Cluster One”, is signed by Gilmour and Wright, progresses with Gilmour’s emotionally wrenching electric guitar and Wright’s sonorous and simple keyboards. For a long time the song is a duet of Gilmour and Wright, but then Mason’s lazily languid, or rather very floyd-like, drums join in. ”Marooned” is nice enough, but again largely a one-idea instrumental with a hint of magic thanks to Gilmour’s gorgeous guitar sound. The song was Grammy-worthy as ”Marooned” was awarded the Grammy for Best Instrumental Song. It is, by the way, Pink Floyd’s only Grammy award. Quite baffling.

”A Great Day for Freedom” is a cinematic anthem where the urgent piano is joined by strings delicately arranged by Michael Kamen. The listener is again treated to a fine guitar solo where Gilmour stretches and waxes his simple notes gracefully at will as if by the power of telepathy.

Read also: Pink Floyd – Meddle (1971)

The sixth track on the album is composed by Wright and is the highlight of the album so far. Wright’s almost seven-minute ”Wearing The Inside Out” is a slow and mournful, slightly jazzy ballad sung by himself. It’s Wright’s first vocal performance in a lead role since The Dark Side Of The Moon! Wright sings the autobiographical lyrics in a suitably weary voice that has seen the world. Anthony Moore (Slapp Happy), who wrote the lyrics, seems to get inside Wright’s head perfectly. The lyrics chronicle the slow rise of Wright, who suffered from drug problems and inferiority complexes, from the depths of depression. Jazz overtones are brought in by Dick Parry’s gentle saxophone. Wright’s own Minimoog growls majestically in the song’s first ascent and Gilmour’s electric guitar is given plenty of space at the end. A classy track. Wright returned to a somewhat similar mood on his 1996 solo album Broken China.

Unfortunately, after Wright’s great song, we go straight to the most disappointing song on the album. Composed by Gilmour and Ezrin, ’Take It Back’ is a forced stadium anthem that sounds like poor man’s U2. At six minutes, this ridiculously overlong song would have been better suited to A Momentary Lapse Of Reason or even Gilmour’s bland solo album About Face (1984).

”Coming Back To Life”, composed and written by Gilmour alone, returns the album thematically to the ”Wearing The Inside Out” sector.

Pink Floyd didn’t even try to come up with an overarching concept for the album this time (Wright has regretted this afterwards, but it’s not known if he had any suggestions), but there are still certain recurring themes. Many songs refer to the ghosts of the past (for better or worse), reflect on communication, or rather the lack of it, and figuratively return from the dead.

”Coming Back To Life” continues this theme of rejuvenation started by ”Wearing the Inside Out”. However, where there was a faint light at the end of the tunnel in Wright’s mournful composition, Gilmour’s ”Coming Back To Life” is already on the euphoric side. Gilmour’s free-flowing electric guitar successfully captures the elation of a survivor, while Mason’s dull, and more or less repetitive, drum beat traps the song in the ground. This song could definitely have used a more swinging and agile drummer.

At the beginning of the article I criticised The Division Bell for stripping away the surprising elements that often made Floyd’s music so distinctive. However, ”Keep Talking”, co-written by Gilmour and Wright, offers a rather clever little trick. In its chorus, it uses the voice of physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking (interestingly, in the same year Yes also referred to Hawking on its album Talk) processed through a speech synthesizer. Gilmour’s ’talking guitar’ provides a continuum for synthetic speech. Gilmour transforms the sound of his electric guitar into a tube connected to an amplifier with his mouth by making a sound. This so-called talk nox method was popularised by Peter Frampton in the 1970s. The sound of ”Keep Talking” is also more ”technological” than average, as the programmed drums raise their ugly head for the first time in this song. Maybe Gilmour got tired of Mason’s loitering style… just kidding. However, things get a lot better when Mason’s drums show up to stomp alongside the machines. The song also features a nice lilting Minimoog solo that again refers directly to the Wish You Were Here days.

Gilmour’s ”Lost For Words” seems lyrically to hark back to his disputes with Waters. Or maybe it’s something else entirely, but at least the lyrics dealing with the mutual feelings of bitterness between the two parties and the difficulty of reconciliation are juicy to link to the power struggle between the two alphas for Floyd’s dominance.

Musically, the song is driven by an acoustic guitar that alternates between a ringing and a slightly more jarring sound, and is related to Wish You Were Here’s title track. Of course, it does not reach the same magical and seductive levels. However, the ringing bells in the mid-song sound effects section (which also remain almost inaudibly chiming at the bottom of the mix) cleverly hint at the song that follows.

So I open my door to my enemies

And I ask could we wipe the slate clean

But they tell me to please go fuck myself

You know you just can’t win

The album ends with the longest and best song on the album. The eight-and-a-half-minute ”High Hopes” opens with church bells that have already begun to ring in ”Lost For Words”, joined by birdsong and simple piano stabs by Jon Carin. The mood is cleverly transported to England, and more specifically to Cambridge, where Pink Floyd was born in the 60s and where its members grew up searching for their place in the world.

Gilmour’s composition builds from harmonically very simple ingredients a truly courageous atmosphere that is a mixture of golden nostalgia and an almost inescapable faith in destiny. The grass was greener, the lights were brighter and with friends, one way or another, the world would be conquered.

The song’s elegantly understated uplift features marching drums and two acoustic guitars alternating with a backing string orchestra. At the end, as has become customary, Gilmour’s electric guitar is allowed to join in, but the cliché is now turned into a triumph, so powerfully does the maestro infuse his instrument with emotion. ”High Hopes” is a great, great song and in my opinion the only composition of Gilmour’s period that can be ranked among the true Pink Floyd classics. What’s particularly great about it is that it doesn’t sound like any of the band’s earlier songs, yet somehow feels perfectly like Pink Floyd music. It’s a great way to end an otherwise uneven album.

Read also

- Levyarvio: Jimmy Page – Outrider (1988)

- Review: Brian Eno + David Byrne – My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1981)

- Levyarvio: Gong – Zero To Infinity (2000)

- Review: Michael Oldfield – Heaven’s Open (1991)

- Review: Talk Talk – The Colour Of Spring (1986)

- Levyarvio: Jeff Wayne – Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version Of The War Of The Worlds (1978)

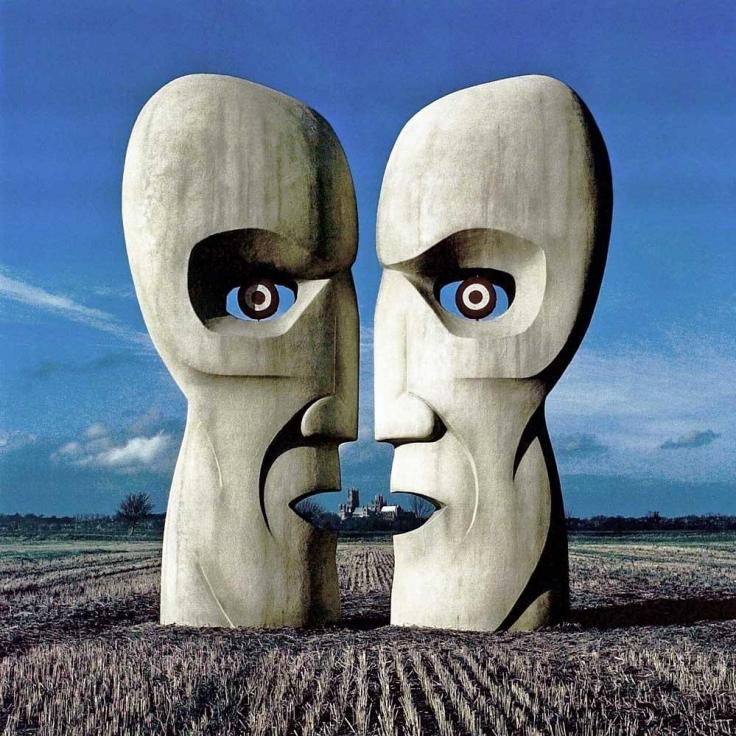

The Division Bell’s cover was a spectacular production, typical of designer Storm Thorgerson. Two huge metal heads were erected in a field to reflect the album’s theme of communication. The two side profiles, talking (or smirking?) to each other, together formed the third ’absent’ face Thorgerson used to refer to Barrett. Perhaps the two side profiles then belong to Gilmour and Waters? And that’s not all, as separate stone heads were built for the C-cassette version of the album to execute the same concept. No expense was spared!

Packaged in Thorgerson’s handsome covers, the album was a big success, as expected. It sold double platinum in the UK and triple in the US. In total, the album is estimated to have sold over seven million copies, not quite matching the 10 million sales of A Momentary Lapse Of Reason.

After the release of The Division Bell, rumours of ”The Big Spliff” sessions were rife among Pink Floyd fans for years. During these sessions, which have gained mythical fame, Floyd was rumoured to have recorded ambient or even space rock material during The Division Bell, resulting in an hour-long composition called ’The Big Spliff’. Eventually it turned out that ”The Big Spliff” sessions were indeed real. They were never released in their original form, but in 2014 this material was further developed into an album called Endless River. Unfortunately, Endless River shows that ”The Big Spliff” jams remained a rather flat and uninteresting ramble. It would probably have been more interesting if these more ethereal and floating parts had been implanted into the songs of The Division Bell.

The Division Bell is almost constantly pleasant to listen to, but only on a few occasions does it really impress. The album’s two best tracks, ”Wearing The Inside Out” and ”High Hopes”, interestingly reach for something completely new while still sounding natural enough to be worthy of the legendary Pink Floyd name in good conscience. In a way, it’s a shame that The Division Bell was the last Floyd album of all-new material by Gilmour and company, because it feels like the next album could have been a smash hit. On the other hand, it would have been even better if Waters and Gilmour had managed to patch things up and make another album together. In 2005, Waters, Gilmour, Wright and Mason did at least have a brief reunion on the concert stage at Live 8, a charity event. But this was a brief moment of reconciliation, as today relations between Waters and Gilmour are once again very sour.

Under David Gilmour, Pink Floyd didn’t reach very high artistic heights, but at least he managed to establish the band as one of the biggest giants in rock history. It was under Gilmour that Pink Floyd rose to a platform from which they will never fall.

Author: JANNE YLIRUUSI

Read also Nick Mason – Nick Mason’s Fictitious Sports (1981)

Tracks

- ”Cluster One” 5:56

- ”What Do You Want from Me” 4:22

- ”Poles Apart” 7:03

- ”Marooned” 5:30

- ”A Great Day for Freedom” 4:16

- ”Wearing the Inside Out” 6:49

- ”Take It Back” 6:12

- ”Coming Back to Life” 6:19

- ”Keep Talking” 6:11

- ”Lost for Words” 5:15

- ”High Hopes” 8:31

Pink Floyd

David Gilmour: lead vocals (2, 3, 5, 7-11), acoustic, electric, classical & steel guitars, bass guitar (3, 5, 10, 11), keyboards, programming, backing vocals, talkbox, production, mixing Nick Mason: drums, percussion, church bell (11) Richard Wright: piano, organ and synthesisers, lead vocals (6), backing vocals (2)

Other musicians

Jon Carin: piano, keyboards, programming, arrangements (10) Guy Pratt: bass guitar (2, 4, 6-9) Gary Wallis: percussion (8), programming (9) Tim Renwick: additional guitars (3, 7) Dick Parry: tenor saxophone (6) Bob Ezrin: percussion, keyboards (3, 7), production Sam Brown: backing vocals (2, 6, 7, 9) Durga McBroom: backing vocals (2, 6, 7, 9) Carol Kenyon: backing vocals (2, 6, 7, 9) Jackie Sheridan: backing vocals (2, 6, 7, 9) Rebecca Leigh-White: backing vocals (2, 6, 7, 9) Stephen Hawking: vocal samples (9)

Thank you for your thoughtful review. Your reactions to the album are similar to mine but I could never describe them so well. I hadn’t realised that Rick Wright had only been given an inferior deal. And yes what a tragedy they and Waters were unable to make peace enough to work together again.

TykkääLiked by 1 henkilö

Thanks for the compliments and thanks for reading! 🙂

TykkääTykkää