A Momentary Lapse Of Reason is Pink Floyd’s 13th studio album.

The making of Pink Floyd’s previous album, The Final Cut, had been a contentious experience and relations between Roger Waters and the rest of the band had been poor for years. Waters had been arguably the most important member of the band’s most successful era since The Dark Side Of The Moon. He had not only conceived the underlying concepts for the albums, he had written all the lyrics, composed most of the material and, increasingly, sang the main vocal parts. After The Final Cut, it had become clear to Waters that he no longer wanted to work with guitarist David Gilmour and drummer Nick Mason. Pink Floyd’s founding keyboardist Rick Wright had already been ejected out of the band by Waters during The Wall sessions.

After The Final Cut, Pink Floyd just seemed to fade away. The band didn’t go on tour and the members didn’t seem to have much contact with each other. About a year after the release of The Final Cut, Waters, Gilmour, Mason and Pink Floyd’s manager Steve O’Rourke met in a Japanese restaurant to discuss their many differences. The dinner went surprisingly smoothly, perhaps too smoothly, as in the end the parties were left with a completely opposite view of what was actually agreed. Gilmour and Mason imagined that Pink Floyd would continue as before once Waters’ The Pros And Cons Of Hitch Hiking album was released. Waters, on the other hand, thought his message had got through; Pink Floyd no longer existed.

A little later, Waters wanted to get rid of O’Rourke, but this would have required the consent of the whole band, which Gilmour and Mason did not have. Waters was also irritated by the ever-increasing demands of the record company for a new album. Or ’product’ as Waters contemptuously phrased the label’s demands. Waters decided to kill two birds with one stone. He would resign from Pink Floyd which would not only free him from O’Rourke but also from his obligations to the label. And since Waters did not believe that Gilmour and Mason would dare, or even be able, to continue as Pink Floyd, he automatically thought that the band would be finished with this move.

In October 1986, Waters filed a claim in the High Court that the Pink Floyd name could never be used again. Gilmour opposed the decision. The court’s decision would have to wait a long time. In December, Waters publicly announced that Pink Floyd was ” spent force creatively” and that the band would no longer exist. This particularly rattled Gilmour and he began planning his next move.

Gilmour’s second solo album About Face, released in 1984, had not sold well and he had been forced to play to half-empty halls on a tour built around the album. It had become clear to Gilmour that without the Pink Floyd brand he would be in trouble. Gilmour has admitted that he felt he had worked so hard for Pink Floyd that he was no longer ready to start from scratch in middle age. When it came time to start working on his next album, Gilmour felt more and more strongly that perhaps it should be released under the Pink Floyd name.

Nick Mason, meanwhile, had released a little-noticed album called Profiles with 10cc/Mike Oldfield guitarist Rick Fenn. Gilmour appeared as guitarist and vocalist on one track on the album and that collaboration prompted them to discuss making a joint album. Prior to Mason’s involvement, Gilmour had been working on music with keyboardist Jon Carin for several months. Gilmour had met Carin, who was just over twenty, while playing in Live Aid with Bryan Ferry’s band. Carin would become a long-time member of Pink Floyd’s touring line-up.

As producer, Gilmour was able to attract Bob Ezrin, who had done a great job on The Wall and had also produced About Face. This angered Waters even more, as he himself had been in preliminary talks with Ezrin about producing his next solo album. In fact, Ezrin even accepted the job, but then backed out at the last minute. Waters saw Ezrin’s defection to the Gilmour camp as a betrayal and a personal insult, although in practice Ezrin’s choice apparently boiled down to the fact that to make Waters’ record he would have had to move his family to England for an extended period. The Gilmour project offered Ezrin more flexible schedules and working conditions. However, Waters was still annoyed five years later, as his 1992 solo album Amused To Death features the bitter lyric ’Each man has his price Bob, and yours was pretty low’. Ouch!

Gilmour, Mason and Carin set about recording A Momentary Lapse Of Reason (Of Promises Broken, Signs Of Life and Delusions Of Maturity were mooted as alternatives, but were judged too easy targets for Waters’ ridicule) in a riverboat moored on Gilmour’s Thames, which had been converted into a high-quality studio. The music was constructed using modern computer sequencing, with copious use of synthesizers and rhythm tracks mostly handled by drum machines. Gilmour, of course, played the guitars and Ezrin played the interim bass tracks. The keyboard playing was shared between Carin, Gilmour and Ezrin.

Mason apparently played some of the drum tracks, but they were mostly wiped out in favour of studio drummers’ performances when the recording sessions moved to Los Angeles. Gilmour has said that Mason was ”catatonic” and virtually incompetent. As a reason for Mason’s collapse, Gilmour has suggested that Waters’ dictatorial behaviour had crushed Mason’s confidence and robbed him of his playing skills. However, Gilmour’s claim does not stand up to closer scrutiny, as in 1987 Michael Mantler’s concert album Live, recorded in February of the same year, was released and Mason plays quite competently and even manages to survive, so to speak, the original parts played by master drummer Jack DeJohnette. Whatever the reason, Nick Mason concentrated on building up the sound effects on the album and his playing is not heard at all on most of the songs. And when you do, it’s mostly in the background percussion. Sad. Especially as the session drummers Jim Keltner and Carmine Appice, who replace Mason, don’t really manage to play anything particularly interesting either. Apart from the ”real” drums, which themselves seem to be almost entirely electric, the album also contains a lot of programmed rhythms.

Studio musicians and outside producers were a familiar sight on Pink Floyd albums from The Wall onwards, but Gilmour takes the use of ”guest labour” to a new level with A Momentary Lapse Of Reason. In addition to an army of studio musicians (17 guest musicians play/sing on the album), Gilmour also enlisted the help of other musicians to write lyrics and music. In fact, he even went in search of a theme with outside help.

Gilmour tried to hunt down a concept for the album, and toyed with Eric Stewart (10cc), poet Roger McCough and Canadian songwriter Carole Pope, but nothing satisfactory came of it. Eventually Gilmour gave up and decided that there was no need for a leitmotif and the songs could stand on their own. A Momentary Lapse Of Reason would become Pink Floyd’s first studio album in 14 years without a unifying theme (the river still recurs as a kind of metaphor throughout the album’s lyrics). Three of the lyrics were delegated to Anthony Moore to write. Moore had previously been a member of Slapp Happy and Henry Cow, and at one time even shared the same management company as Pink Floyd.

Alongside Stewart’s sessions, Gilmour also experimented with songwriting with Roxy Music guitarist Phil Manzanera and 10cc’s Eric Stewart. In the end, only one song written with Manzanera ended up on the album. Ezri, Carin and keyboardist Patrick Leonard also received one shared composition credit. Neither Mason nor Rick Wright, who was included at the last minute, can be found in the songwriting list.

Wright had been available for a long time. Wright’s wife had begged early on in the project to find a place for him in the band, but Gilmour had reservations. After all, she and Mason had invested a fair amount of their own money (Mason even mortgaged his Ferrari) to get the project off the ground. And they didn’t really need more partners to share the spoils. Especially as there was no guarantee of Wright’s playing ability. In the end, however, Wright was invited to join in at the very end of the recording sessions, but only as a guest. Wright’s contribution was minimal: he sang a few vocal harmonies on the album and played a little Hammond organ in the background on a couple of songs (it’s not easy to spot those parts!). He also played a solo on ”On The Turning Away”, but this was omitted in the final mix. It seems clear that Wright was included to make Gilmour and Mason’s Pink Floyd hijacking look better to the public and perhaps make their case against Waters stronger in court. Amusingly, keyboardist Tony Kaye was brought back into Yes for very similar reasons when the band made a comeback with 90125 four years earlier. The 80s was an era of artificiality and that was often true of band line-ups.

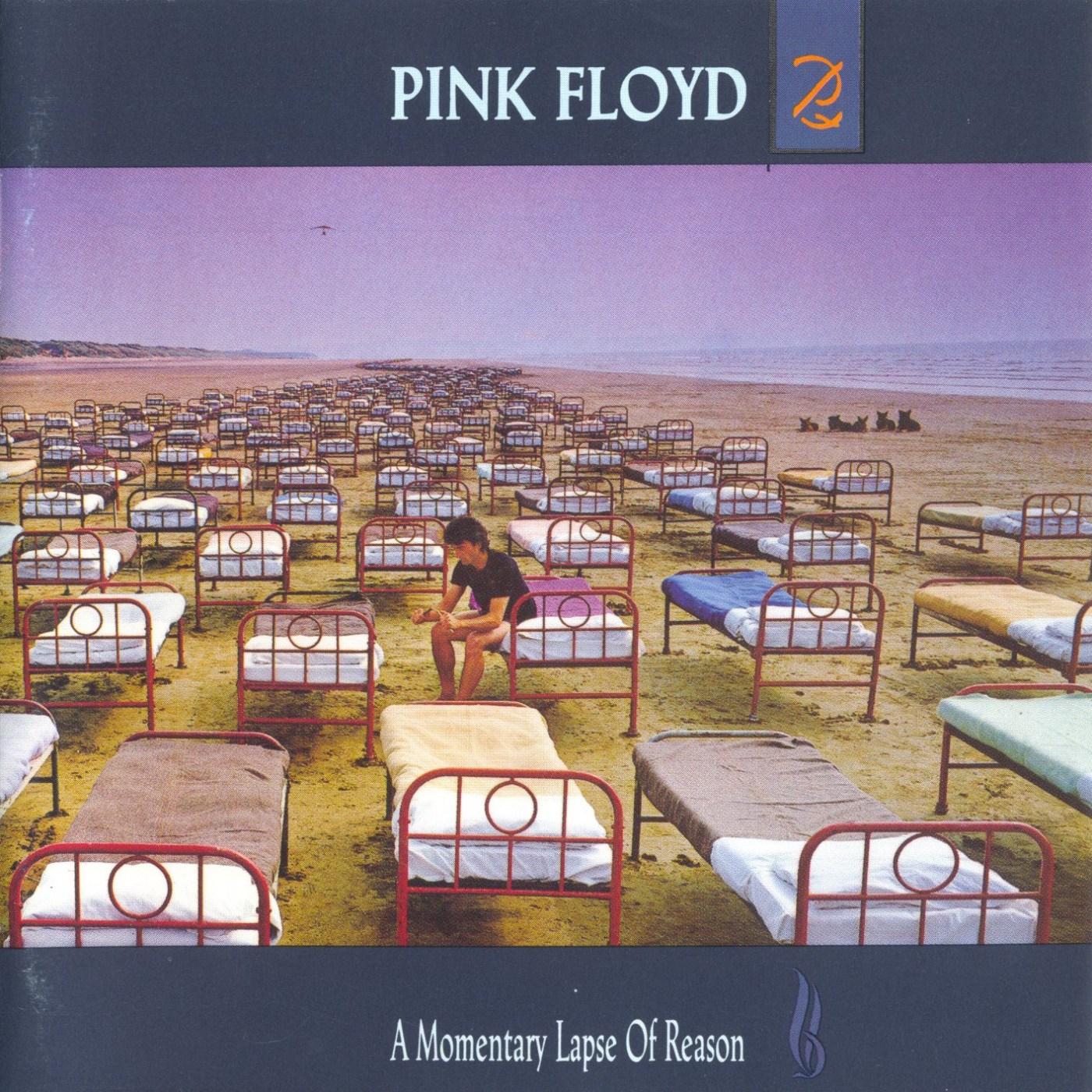

Another major figure from Pink Floyd’s past was recruited for the project. Cover designer Storm Thorgerson, who had designed Pink Floyd’s covers for Hipgnosis before The Wall, was commissioned again. Thorgerson took the recurring river theme in the lyrics and built on it to create a stunning cover with 800 hospital beds meandering like a river along a sandy beach. The cover is particularly impressive because the image is not some cheap photo manipulation, but Thorgerson and his team actually dragged the beds onto the beach for the shot. You can sense this authenticity in the image and it gives it a power that even the best version built in image editing software couldn’t match.

Read also: Porcupine Tree: Closure/Continuation (2022)

The album begins with the ethereal instrumental ”Signs Of Life. An ambient collage of mostly sound effects and synthesizers with a bit of Gilmour’s heavily echoed electric guitar at the end. ”Signs Of Life” clearly tries to fulfil the same function as the long intro of ”Shine On You Crazy Diamond”, but it falls far short of the same magic and the four-minute instrumental feels much longer than its duration. And that’s just in a bad way.

One of the funniest stories about the album is an anecdote about how record company CBS representative Stephen Ralbovsky reacted to Gilmour’s first demos. Ralbovsky bluntly informed Ezrin and Gilmour that ”this music doesn’t sound a fucking thing like Pink Floyd” and sent the men back to the studio. I’m guessing that ’Signs Of Life’ may well be one of the direct reactions to that harsh comment.

The album’s second song ”Learning To Fly”, the first single to be released as the album’s lead single, is a reasonably catchy pop song that is very reminiscent of music on the Gilmour’s second solo album About Face. There’s nothing particularly Pink Floyd-esque about the straightforward and simple song, except of course for Gilmour’s electric guitar, which again sounds beautiful. Rhythmically the song is dead on its feet. The electronic drums, which are loosely rollicking, are boring to listen to. The lyrics of ”Learning To Fly” literally describe Gilmour and Mason’s shared hobby of flying. The description of the gentlemen’s environmental crime was outsourced to a hired hand, though, and the vacuous lyrics were written by Anthony Moore.

The third track ”The Dogs Of War” is the highlight of the album. At six minutes, ”The Dogs Of War” is a mechanical blues, pulsating in a mostly slow 12/8 time signature that feels like a distant relative of ”Welcome To The Machine”. It adds a hint of edge to the album and has a touch of Waters-like bitterness to its theme. Unfortunately, the lyrics, written by Moore about vile politicians who instigate wars for money and power, remain rather tepid and would have required some meat on their bones.

”The Dogs Of War” features a nice dirty saxophone solo in a section that, slightly reminiscent of ”Money”, jumps into a rocking 4/4 time signature.

I understand that ”The Dogs Of War” is the quite hated song among Pink Floyd fans. I remember it was even voted the weakest track in the band’s history in a major fanzine, Brain Damage. I strongly disagree. I think ”The Dogs Of War” is the most successful track on the album and one that showed a possible new direction but with a hint of the old Pink Floyd genes. The sterile hi-tech soundscape of the album also fits ”The Dogs Of War” better than many of the other tracks on the album.

Opening with vague video game-like bleeps, ”One Slip” turns the 80s influence on full blast. Co-written with Phil Manzanera, the song is a real blockbuster that feels tailor-made for listening in an expensive sports car with the sleeves of a pastel coloured blazer rolled up. The song is defined by stiffly pounding electric drums and Gilmour’s enthusiastic vocal performance. Towards the end, Tony Levin’s Chapman Stick is brought to the surface, which adds a little interest, but something strange has been done to his sound too: the usually gorgeous-sounding Levin’s playing is somehow mechanical.

The fifth track ”On the Turning Away” is a slightly Celtic-sounding, harmonically very simple, ballad. It’s a very typical 80’s world-saving song with corporate pop stars flying around the planet in private planes to clear their consciences. The lyrics declare in platitudes that ’we will not turn our backs’ on the world’s problems. Ah, well nice. Well to Gilmour’s credit, however, he has subsequently used his vast fortune to contribute to a number of charitable causes. That doesn’t save this song, but on the other hand the long electric guitar solo at the end with Gilmour’s massive sound is impressive and one of the best moments on the album.

”On the Turning Away” closes the A-side of the album. Unfortunately, the B-side is even more subdued than the first.

Composed with keyboardist Patrick Leonard, ”Yet Another Movie” successfully paints a cold and chilly mood and contains the most vivid moment of the whole album in the middle when it comes to drumming. And lo and behold when I did some research for this article it turns out that this is apparently the only part of the album where good old Mason lets loose with his drum kit! Perhaps Mason should have been let out to tend the engine room a little more often after all.

The album’s most tiresome offering is the instrumental track ”Terminal Frost” and the tuned around it ”New Machine Part 1” and ”Part 2” which are based on Gilmour’s boring vocoder song. The stagnant ”Terminal Frost” strums and thumps lazily for six minutes and leaves no lasting impression. John Helliwell’s (Supertramp) saxophone takes centre stage. With varying degrees of success. ’Terminal Frost’ had been composed years earlier and was intended to end up on Gilmour’s third solo album.

A Momentary Lapse Of Reason ends with its longest song, the two-minute ”Sorrow”. It’s a bit of a frustrating case because ”Sorrow” is a composition that would have had the potential to be a masterpiece of the album, but which falls a bit flat due to its arrangement. Gilmour is said to have put the song together single-handedly over a weekend at Astoria and apparently added nothing later than a smattering of Wright synthesizers, Levin’s bass guitar and some backing vocals. The song is cramped by a really cumbersome and clumsily programmed rhythm track. No real drummer was used at all. Despite its lumbering execution, ’Sorrow’ has genuine drama and its poetic lyrics effectively explore the themes of grief and loss. The song is strongly supported by Gilmour’s electric guitar, which alternates between soaring and snarling.

Lue myös

- Review: Rush – Moving Pictures (1981)

- Review: Pavlov’s Dog – At The Sound Of The Bell (1976)

- Levyarvio: Pavlov’s Dog – At The Sound Of The Bell (1976)

- Levyarvio: Godspeed You! Black Emperor – Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas To Heaven (2000)

- Year by Year: Best Albums of 1975 – 1-10

- Levyarvio: Kansas – Somewhere To Elsewhere (2000)

Paradoxically, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason sounds too much and too little like Pink Floyd. It makes a vague reference to the band’s illustrious past and at the same time its new innovations are mainly related to a soundscape that has been attempted to be tuned up to the latest state of the art. Unfortunately, while Pink Floyd’s golden age was defined by their wonderfully timeless, hi-fi soundscapes, it’s a huge shame that Ezrin and Gilmour didn’t manage to do even that, and instead made the mistake of screwing the sound too much with the worst trends of the 80s, condemning it to instant obsolescence. It seems that Gilmour himself agrees, as a remix of the album was released in 2019, where it has been stripped down as much as possible. It was an interesting experiment, but I was surprised how little it improved the album in the end.

A Momentary Lapse Of Reason is a safely mediocre million dollar (an understatement for sure!) product for stadiums. The equivalent of a giant Hollywood blockbuster that fills movie theatres for a while and increases popcorn sales by 200%, but leaves no lasting impression. A Momentary Lapse Of Reason lacks the provocativeness and a certain mystique of Pink Floyd’s earlier albums. Of course, the psychedelia and avant-garde influences of the early days had long since disappeared, so it was no fair to expect them.

Roger Waters called the album a ”clever forgery” and criticised the songs in general as poor and Gilmour’s lyrics as unimaginably unclassy. Which is actually a surprisingly gentle characterisation from a man known as a very strident commentator. Funnily enough, Richard Wright has subsequently acknowledged that Waters was right. Gilmour himself has said that this is not Pink Floyd’s best album, but that he did his best to restore the balance of music and lyrics that he felt had tipped too far to the latter under Waters’ dominance.

It is interesting that when talking about A Momentary Lapse Of Reason’s predecessor The Final Cut, it is very common to label it as ”just a Roger Waters solo album” instead of a proper Pink Floyd album. And that’s fine, there are good reasons for that view, I don’t deny that, but I just wonder why A Momentary Lapse Of Reason is rarely referred to as ”just David Gilmour’s” solo album. Because that’s what it really is in the light of all the facts. The Final Cut, after all, featured three long-time Pink Floyd members throughout the album, but A Momentary Lapse Of Reason features at least 90% of the music played by Gilmour and an army of studio musicians, with an extraordinary amount of help from outside the band for the composition and lyrical work.

Waters and Gilmour’s dispute was finally settled out of court at Christmas 1987. It is unclear what all the agreement contained, but apparently Waters was granted extensive rights to The Wall and Gilmour and co. were allowed to continue unhindered under the Pink Floyd name. A happy ending? No, it wasn’t. The bitterness on both sides still lives on almost 40 years later.

Surprisingly or not, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason was a great success. In the plastic pop music environment of the 80s, there was clearly room for one more plastic-wrapped dinosaur. Gilmour’s Pink Floyd joined the ranks of 70s prog bands like Genesis and Yes that managed to sell themselves to a new audience while at the same time retaining at least some of their old fans. A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, with sales of ten million, did not reach the level of mega-hits like The Dark Side Of The Moon and The Wall, but it sold far better than its predecessor The Final Cut. And most importantly for Gilmour and Mason, Waters’ solo albums were left far behind (especially the artistically and commercially unsuccessful Radio K.A.O.S.). Gilmour had successfully seized control of Pink Floyd and outperformed his nemesis in both record sales and concert performances. In the cold war between Gilmour and Waters, which continues to this day, Gilmour was leading 2-0 for the time being.

Best songs: ”The Dogs Of War”, ”Sorrow”

Read also: Pink Floyd: The Final Cut (1983)

Author: JANNE YLIRUUSI

Tracks

- Signs of Life – 4:24

- Learning to Fly – 4:53

- The Dogs of War – 6:05

- One Slip – 5:10

- On the Turning Away – 5:42

- Yet Another Movie – 6:13 6a) Round and Around – 1:13

- A New Machine (Part 1) – 1:46

- Terminal Frost – 6:17

- A New Machine (Part 2) – 0:38

- Sorrow – 8:45

Pink Floyd

David Gilmour: vocals, guitars, keyboards, sequencers Nick Mason: electronic and acoustic drums, voice, sound effects.

Other musicians

Richard Wright: backing vocals, piano, Hammond organ, Kurzweil synthesizer Bob Ezrin: keyboards, percussion, sequencer, production Jon Carin: keyboards Patrick Leonard: synthesizers Bill Payne: Hammond organ Michael Landau: guitar Tony Levin: bass guitar, Chapman Stick Jim Keltner: drums Carmine Appice: drums Steve Forman: percussion Tom Scott: alto sax, soprano sax John Helliwell: sax Scott Page: tenor sax Darlene Koldenhoven: backing vocals Carmen Twillie: backing vocals Phyllis St. James: backing vocals Donny Gerrard: backing vocals

Jätä kommentti