Ommadawn is Mike Oldfield’s third studio album.

Following Oldfield’s huge surprise success with Tubular Bells, Hergest Ridge was a challenging album to make. Oldfield had been somewhat reluctant to make the album, pressured by his record company, and although the end result was excellent, the album received a mixed reception compared to Tubular Bells. However, the sensitive Oldfield felt that the reception was not mixed, but simply judgmental.

This upset him greatly, and even though Hergest Ridge is in many ways a better album than Tubular Bells, the negative critical feedback shook Oldfield’s confidence to such an extent that he himself began to question the merits of the album and his own abilities in general. For a while… but he set out to make Ommadawn with enthusiasm. And this time he wanted to do everything himself: produce, record, and, of course, play most of the instruments. And all this in his own studio, which was installed for Oldfield in his house in Herefordshire. In the basement studio of his home, he worked alone on Ommadawn for almost a year, occasionally inviting guests to play on the album.

At the time of recording Ommadawn, Oldfield, who was only 21 years old, was not doing well. He drank too much, was anxious, and suffered from devastating panic attacks. However, making music kept him sane and was a kind of escape from the real world.

A new setback came in the middle of the recording sessions with the news of the death of his mother Maureen, who had suffered from mental health problems for a long time. This was a heavy blow for Oldfield, but after a short break, the recording continued and he channeled all his pain into his music. Oldfield himself has stated that he makes better music when he is feeling unwell, and this pattern is clearly evident when you look at Oldfield’s output more broadly and know a little about the twists and turns of his personal life. In the case of Ommadawn, this theory certainly holds true: Oldfield was probably at a low point in his life, but the music he created was his strongest to date.

Oldfield basically recorded the album twice. The first attempt failed when the tapes Oldfield used began to deteriorate, either because there was something wrong with the quality of the tapes, or perhaps because Oldfield used the tapes too many times, erasing them and recording new parts. A couple of months of work went to waste, and Oldfield had to start almost from scratch. This was another serious setback for Oldfield, but he eventually got back on track and ultimately felt that the failure of his first attempt was actually a blessing in disguise, as the new version of the album turned out much better than it would have been without the new recording session.

Read also:

- Review: Michael Oldfield – Heaven’s Open (1991)

- Review: Talk Talk – The Colour Of Spring (1986)

- Levyarvio: Jeff Wayne – Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version Of The War Of The Worlds (1978)

- Review: Gong – Shamal (1976)

- Review: Genesis – A Trick Of The Tail (1976)

- Review: Rush – Moving Pictures (1981)

- Review: Pavlov’s Dog – At The Sound Of The Bell (1976)

- Levyarvio: Pavlov’s Dog – At The Sound Of The Bell (1976)

- Levyarvio: Godspeed You! Black Emperor – Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas To Heaven (2000)

Ommadawn continues in the unique symphonic rock style of Oldfield’s two previous albums. Ommadawn also borrows its format from previous albums, as it consists of two long compositions, each lasting half of a vinyl record, similar to Tubular Bells and Hergest Ridge. Ommadawn even mirrors Tubular Bells in hiding a small separate song at the end of the latter epic. In the case of Tubular Bells, it was an arrangement of the traditional ”Sailor’s Hornpipe,” and for Ommadawn, Oldfield composed a three-minute light song called ”On Horseback.”

Hergest Ridge Oldfield’s music had begun to take on Celtic influences. These characteristics are further reinforced on Ommadawn, but they are also seamlessly combined with other ethnic influences, such as African drumming and Greek and Eastern European tones. Ommadawn was, in a sense, world music before the term had even been coined. However, the ethnic influences blend naturally into Oldfield’s own musical language, and the end result never sounds like a forced mixture of Western pop music and ethnic exoticism.

Oldfield avoids the ”pop meets ethno” clichés, partly because in 1975 such a template had not yet been created, and partly because his own way of composing music just happened to be very original. His music had very little to do with Western pop music. Oldfield himself listened mostly to classical music (Sibelius was his favorite) and drew inspiration from the style of great symphonies. The sound of Ommadawn is even more orchestral than Oldfield’s previous albums. Hergest Ridge already showed Oldfield’s more developed ability to construct long musical arcs, but Ommadawn, especially ”Part One”, takes this even further. Ommadawn perfectly combines high culture and folk art, as symphonic art music meets folk music through Oldfield’s unique and self-taught compositional pen.

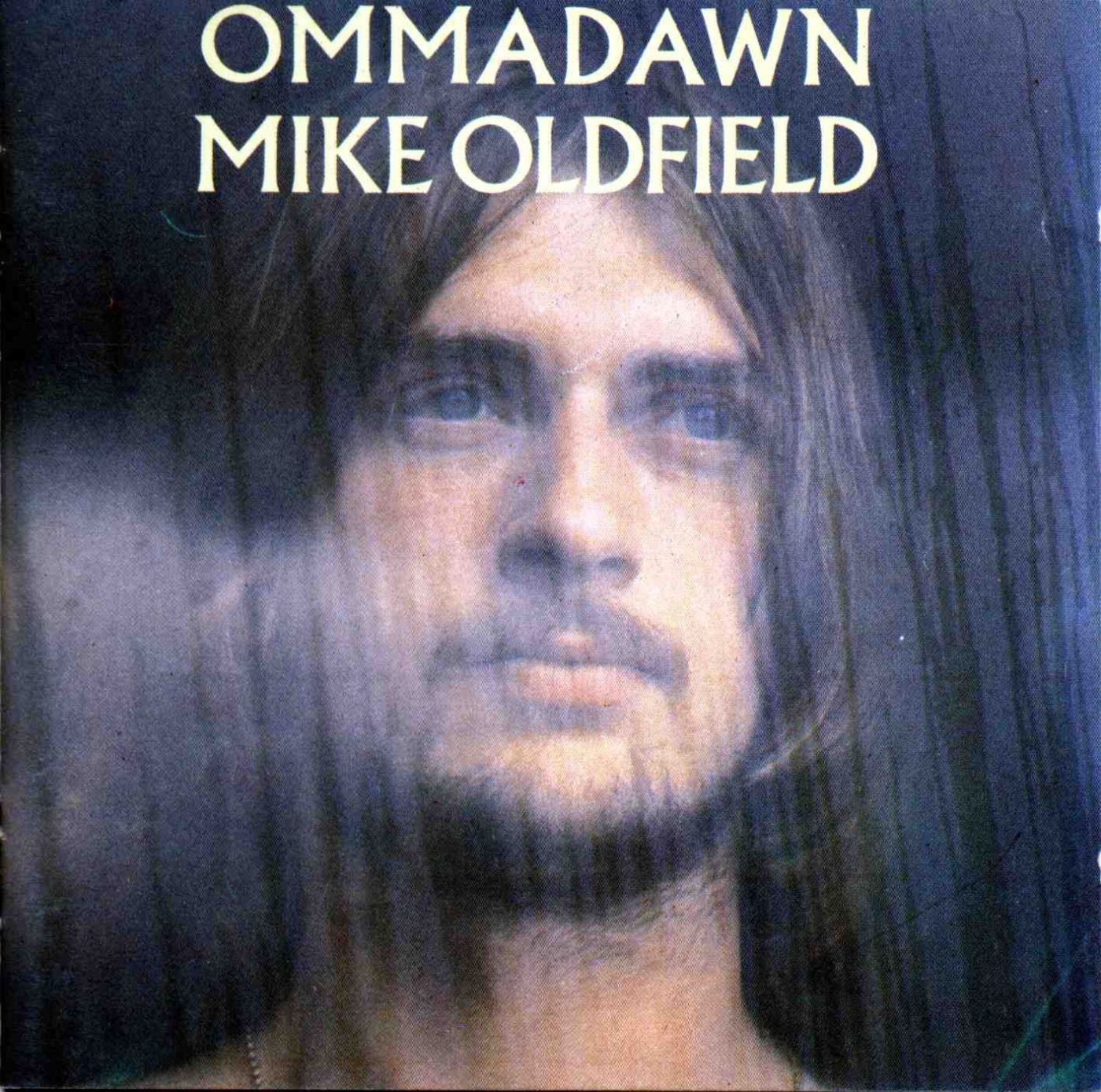

The sound of the album is slightly more acoustic than before. The electric guitar naturally plays a leading role on many tracks, but there is also plenty of room for the harp, recorders, bagpipes, and various acoustic string instruments. Even the electric bass guitar is occasionally replaced by an acoustic bass guitar custom-made for Oldfield by the famous guitar maker Tony Zemaitis. Oldfield himself plays most of the instruments on the album (the album cover lists 19 instruments, the most exotic of which are probably the aforementioned Celtic harp, but also the bodhran and bouzouki). Ommadawn also features a wider range of guest musicians than before. The guest musicians consisted mainly of Oldfield’s friends (of whom he had few) and musicians from the surrounding area, as well as a few more experienced veterans (such as Gong’s percussion master Pierre Moerlen, who plays timpani on the album), who were arranged for the sessions by the record company Virgin.

Ommadawn Part One

Ommadawn begins with a beautiful and somewhat eerie simple melody, on which the entire composition is largely based. Oldfield develops this melody throughout the 19-minute composition and effectively makes the most of it by subtly varying it both musically and instrumentally. At times, the basic melody develops in a wonderful way into a new counter-melody.

At around nine minutes, a short and beautiful cello interlude played by David Strange leads into the album’s first guitar solo. Oldfield’s virtuoso two-minute guitar solo, played with a crisp and sharp sound, picks up the tempo of the song and adds rhythm with Oldfield’s bodhrán (Irish hand drum), as well as introducing vocals for the first time. At this point, it is in the form of wordless choral vocals. At around 13 minutes, Clodadgh Simonds’ (Mellow Candle) vocal part begins, repeating like a spell.

Oldfield asked Simonds to come up with some words to sing in Irish. Simonds spontaneously wrote the humorous lyrics “Daddy’s in bed, The cat’s drinking milk, I’m an idiot, And I’m laughing,” which his relative then translated into Irish. In the Irish lyrics, the word ”amadán” (”idiot”) was translated into the more phonetic form ”omma dawn,” which is how the album ultimately got its name.

Ab yul ann idyad awt

En yab na log a toc na awd

Taw may on omma dawn ekyowl

Omma dawn ekyowl

With the vocals, Oldfield begins to steadily build the music towards a climax, somewhat like at the end of the first half of Tubular Bells, but much more subtly and skillfully.

”I realised that what had been fucking me up was being born. A lot people get fucked up when they’re born. So I decided that I was just going to be re-born. It was the only answer. I had to recreate the circumstances of my birth.” – Mike Oldfield

The absolute highlight of the album is the climax of ”Part Two,” which builds up over several minutes and finally culminates in a breathtaking guitar solo lasting several minutes. At the 16-minute mark, Moerlen’s timpani begin to rumble in the background and Oldfield begins his unique guitar solo, accompanied by a synthesizer and glockenspiel, among other instruments. The solo begins melodically, but then Oldfield changes style, playing intermittently and sharply, sometimes playing just a few striking notes and then continuing with even greater intensity after a short pause. At some point, the African drums of a four-piece group called Jabula join in, playing a central role in supporting Oldfield’s guitar playing.

”The end of the first side of Ommadawn is the sound of me exploding from my mother’s vagina.” – Mike Oldfield

Oldfield’s painfully wailing guitar manages to convey a stormy emotional chaos that would be impossible to describe in words. Oldfield himself believes that he was deeply traumatized by his own birth, and in order to release that trauma, he wanted to recreate that moment of trauma through music. According to Oldfield himself, the guitar solo literally depicts him exploding out of his mother’s vagina. It may not be a vision that I actually associate or want to associate with the music itself when I listen to it, but the emotional charge it contains is overwhelming in any case. In fact, I have never heard anyone play electric guitar with as much soul as Oldfield does in this stunning finale. It is one of the few musical moments that always manages to give me goosebumps.

”It scared me to death when I did it. When I did that electric guitar, I found it really frightening. I couldn’t sleep” – Mike Oldfield

After the roaring climax, the other instruments fall silent and only the African drums remain, beating a persistent rhythm like a pounding heart after orgasm. The song fades out for over a minute as the sound of the drums fades into the distance. An unusual but very effective ending.

Ommadawn Part Two

After a masterful first half, Oldfield has the nearly impossible task of continuing the album without letting the mood deflate. ”Part Two” doesn’t quite reach the level of the first half, but it comes surprisingly close.

”Part Two” begins harmoniously, very statically and almost drone-like. The music, which lingers back and forth for the first few minutes, sounds a bit like it is being played on an organ, but is actually made up of a massive number of overlapping electric guitar tracks (Oldfield claims in his biography that as many as 1,984 guitars were played on top of each other). Oldfield had already experimented with a massive number of electric guitars recorded on top of each other in the legendary ”electric thunderstorm” section of Hergest Ridge, and this is a new application of that idea. The drone-like section eventually ends in a sparkling and dense, jangling guitar texture reminiscent of Terry Riley, after which the music transitions into an airy and very pastoral section.

Oldfield gently strums his acoustic guitar, accompanied by the harp and some kind of organ in the background. Oldfield plays a short interlude on the electric guitar, and the sharp sound of the bagpipes cuts into the soundscape. This marks the beginning of a wonderful duet between the guitar and the bagpipes. Oldfield’s acoustic guitar and gentle organ accompaniment generously make room for Chieftains legend Paddy Moloney (born 1938), who plays Oldfield’s magnificent melody with great empathy and intensity. The five-minute section was recorded quite spontaneously in the wee hours of the night while sipping Guinness. The entire section was recorded in one take, and Moloney, Oldfield, and engineer Phil Newell were truly amazed that the duet, played without any click track, ended up matching the tempo of the next section of music, which had been recorded earlier.

After Moloney and Oldfield’s duet, we hear a beautiful and melancholic recorder solo played by Les Penning (Penning’s recorders play an important role throughout the album), which is followed by a short, impressive electric guitar interlude and then a rhythmic folk dance section, in which Oldfield once again plays a magnificent, virtuosic and intense guitar solo, this time cleverly balancing somewhere between joy and melancholy.

On Horseback

Hidden at the very end of Ommadawn Part Two is a children’s song that is not credited in the liner notes but is commonly known as ”On Horseback.” ”On Horseback” is a delightfully naive and charming little piece, yet it has been produced with the same care and precision as the rest of the album. Oldfield first mumbles and then sings about simple rural joys, mainly horse riding. The idea was probably inspired by Oldfield and recorder player Les Penning’s joint pony rides. Oldfield and Penning used to play medieval songs together in a pub near Oldfield’s home for a glass of wine, but they also often went riding in the moors surrounding Hergest Ridge, and apparently this activity made an impression on Oldfield, as he sings that riding a horse is more enjoyable than flying through space, which is saying a lot from a big Star Trek fan.

Hey and away we go Through the grass, across the snow Big brown beastie, big brown face I’d rather be with you than flying through space.

I like thunder, and I like rain And open fires, and roaring flames. But if the thunder’s in my brain, I’d like to be on horseback Some like the city, some the noise Some make chaos, and others, toys. But if I was to have the choice, I’d rather be on horseback.

In the finale, a children’s choir consisting of four children joins in the song, which works brilliantly. They were apparently just a group of random local children, and their slightly unpolished performance fits perfectly with this very human and easygoing song. ”On Horseback” is a great ending to an otherwise rather serious album, without being a silly comedy number.

I just referred to Ommadawn as a serious album, and it largely is, but to counterbalance all the sadness and outright anger, the album also contains a lot of beauty and pure joy. Ommadawn is a real rollercoaster of emotions and the most emotional album I have ever heard. The music seems to come straight from Oldfield’s soul, and there is nothing artificial or inauthentic about it. I don’t believe that at this stage in his life Oldfield would even know how to fake anything musically, even if he wanted to.

Tubular Bells is, of course, the album for which Oldfield is best known. However, a significant portion of Oldfield’s most enthusiastic fans consider Ommadawn to be the best album of his career. As far as I understand, it is also Oldfield’s own favorite. Oldfield intended to make a sequel to Ommadawn as early as 1990, but in the end, the album, titled Amarok, turned out to be something completely different (and that’s a good thing!), but it does have some features of Ommadawn, such as the massive finale with African drums. However, Oldfield couldn’t stay away from the mood of Ommadawn, and in 2017, the official sequel was finally released, aptly named Return To Ommadawn. It is a fine return to Oldfield’s early ”handmade music,” although it naturally cannot compare to the original.

Oldfield’s fans adore Ommadawn, critics liked the album, and even Oldfield himself was satisfied with his work for once. And me? Well, I simply love Ommadawn. For several decades now, it has been the most important album for me, and I don’t think that will change in the future. Ommadawn is a masterpiece that, in my opinion, cannot be praised enough.

Author: JANNE YLIRUUSI

Tracks:

Side A

”Ommadawn (Part One)” – 19:23

Side B

”Ommadawn (Part Two)” – 17:17 (Sisältää ”On Horsebackin” 3:23)

Mike Oldfield plays:

acoustic bass, acoustic guitar, banjo, bouzouki, bodhrán, classical guitar, electric bass, electric guitars, organ, glockenspiel, harp, mandolin, percussion, piano, spinet, steel guitar, synthesizers, 12-string guitar, vocals

Guests:

Don Blakeson: trumpet Herbie – Northumbrian bagpipes The Hereford City Band: horns Jabula: African drums Pierre Moerlen: timpani Paddy Moloney: Irish bagpipes (Uilleann) William Murray: percussion Sally Oldfield: vocals Terry Oldfield: pan flutes Leslie Penning: recorders Abigail, Briony, Ivan and Jason Griffiths: vocals (”On Horseback”) Clodagh Simmonds: vocals Bridget St John: vocals David Strange: cello

Producer: Mike Oldfield

Label: Virgin

Thank you for yet another insightful , informative and enjoyab

TykkääLiked by 1 henkilö

Great Review!

Towards the end of side 2 you reference ’a short, impressive electric guitar interlude’.

That does not do it justice-

Starting at 11:45 after Les Pennings flute -there is a gradual build up to an explosion of glorious sound which is a reprise of the beginning themes of side 2. The multi-tracked guitars deliver an eerie orchestral blast with cord changes that still make me weep. I’ve listened to this hundreds of times over the years-and it still has the same emotional impact. For me this 45 second section has been Oldfield’s most powerful composition. The original version is still the best and turn the volume way up and be overwhelmed.

TykkääTykkää